A Quick Note

Before we dive in, I feel I should address a few things.

First, I’m going to be rating films featuring Jesus as successful or not based on the number of awards they have received or for which they have been nominated. I understand that one of these films may represent the “truth” for one Christian community or another and might be considered successful for them; however, this does not seem to me to be a reliable indicator of its value comparing it to other films. Similarly, success at the box office is not necessarily indicative of positive critical acclaim, even though it certainly can be indicative of a film’s popularity (which is important, too). Nevertheless, because “Jesus films” are still films, regardless of their content, I feel that this is the fairest way to approach this topic.

Secondly, it’s difficult to analyze any kind of story without examining the entire story, including the ending. So beware of spoilers for most, if not all, of the the films we discuss. And spoilers for a 2000-year-old book, I guess.

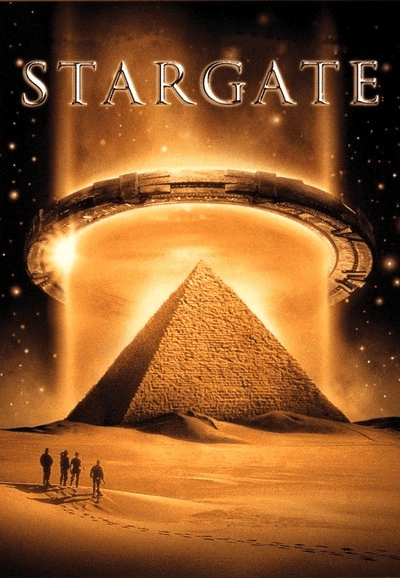

Lastly, I’d like to say at the outset that, if one of the films I’m criticizing is one of your favorites, I’m not trying to personally attack you. As noted above, critical success or a lack thereof does not mean a film is no good. My favorite movie, for instance, is the 1994 sci-fi blockbuster Stargate.

Based loosely on concepts introduced in Erich von Daniken’s book Chariots of the Gods and starring Kurt Russell and James Spader, Stargate has it all: action, adventure, mythology, guns, humor, romance, ancient aliens, a blonde protagonist with glasses whose knowledge of ancient cultures ends up saving the day…. It’s like they wrote it for me.

However, while it definitely tops my personal list of favorite films, Stargate isn’t going to go down as one of the crown jewels of cinema. And that’s ok. I can still enjoy watching Russell and Spader fight the aliens who built the pyramids with lasers without the need for external validation. Similarly, my opinion of these films about Jesus should not in any way dampen what they mean to you, either as movies or as testaments of faith. In fact, when I’ve previously presented this topic as a lecture, I was told to my face by someone in the audience that I was wrong, so I understand how this discussion might ruffle some feathers. Luckily, I was still able to walk away after the lecture and only shed a few tears. My goal is to present this topic in order to foster a healthy and constructive discussion.

With that out of the way, let’s get back to the movies.

The Promise and the Problem

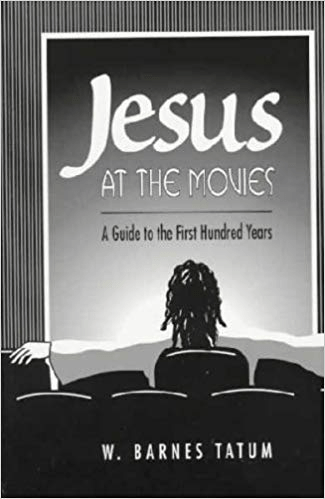

So to review: the end of the grad school semester was fast approaching, and my goal for the final paper was to prove that movies about Jesus were unsuccessful BECAUSE they were about Jesus. When I considered exactly how I would prove this, however, it seemed I would be dealing more with personal opinion than objective fact, even when factoring in individual box office performance or critical acclaim. Luckily, I was able to find a very helpful book appropriately titled “Jesus at the Movies: The First Hundred Years” by W. Barnes Tatum, professor of Religion and Philosophy at Greensboro College.

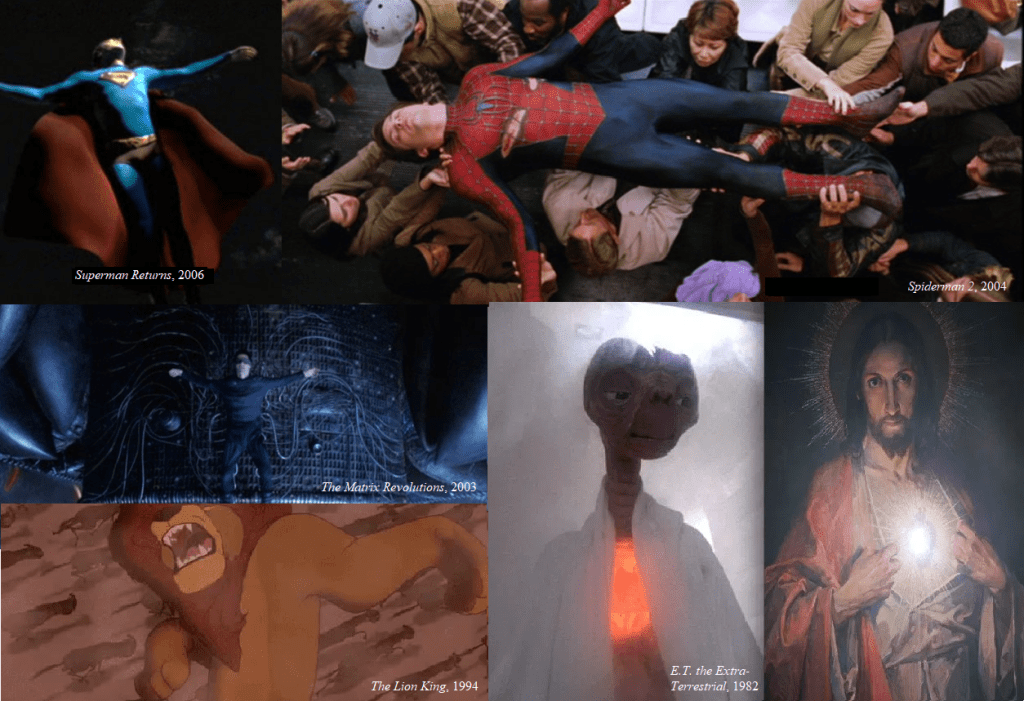

As the title promises, Tatum examines every significant “Jesus film” that had been released up to that point, “from Sidney Olcott’s silent classic From the Manager to the Cross [1912] through Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ [2004].” (The third edition would go on to cover Dornford-May’s Son of Man from 2006.) There are obviously many, many movies that one could incorporate into such a study. It has become common practice for directors to produce movies that allegorically parallel the events of the Gospel story, for example, or movies that follow a Christ-figure who heroically sacrifices himself or herself for the sake of others.

For the sake of uniformity, however, Tatum decides to stick to films that are explicitly about the life, ministry, and death of Jesus as portrayed in the Gospels. While this might appear to be too narrow a restriction on the movies that are studied, we’ll soon see that this smaller list is complicated enough.

Tatum speculates that directors who attempt the daunting task of making a Jesus movie end up having to contend with what he calls the Promise and the Problem of portraying Jesus in the medium of film. Throughout his study, he identifies two Promises and four Problems: the Promises of genre and scholarship, and the Problems of artistic style, literature, history, and theology. We’ll start by examining the two Promises, and then look at the Problems.

The Promise of Genre

The invention of the cameras and the ability to capture motion on film is almost as important to human development as the printing press. If the mass production of books and the written word spread a previously inaccessible amount of knowledge to ordinary people, then film has similarly allowed audiences living decades after an event to experience this event as it really happened. Even paintings or descriptions in literature can only convey so much information about a subject. Though not perfect, film allows us to bring history to life as never before.

Of course, the majority of movies don’t deal with footage of real events, but with stories. Whether or not you think the book is always better than the movie version, I don’t think anyone would argue that the genre of film possesses an inherent capacity to bring stories to life through the use of different aspects of filmography (music, lighting, dramatic and literary arts, etc.) in ways not possible in a book or a play. A camera can present action from different angles and therefore change the meaning of a scene, or be edited to highlight a specific aspect of a scene in way the human eye might not be able to on its own. Even a stage performance, with its energy and three-dimensional presentation, cannot capture action in the same way as a film.

So the medium of film, according to Tatum, naturally holds a great promise for the genre of Christian cinema, especially retellings the life and death of Jesus. Unlike a stage performance, a film can be viewed multiple times in its original form even decades after the initial filming. A film is also always readily available and does not require the coordination of dozens of performers and months of preparation ahead of viewing. For Christians whose only experience in imagining the physical likeness of Jesus comes from seeking descriptions in the Bible (of which there are basically none) or from religious art in churches or art galleries (as historically inaccurate as a blonde-haired, blue-eyed Jesus is), being able to see Jesus walk, talk, preach, heal, and die on a massive screen undeniably adds an important element to what can be a moving experience.

The way in which a director chooses to use the amazing genre of film to portray his interpretation of the Gospel story, however, is another more nuanced matter entirely (more on that later).

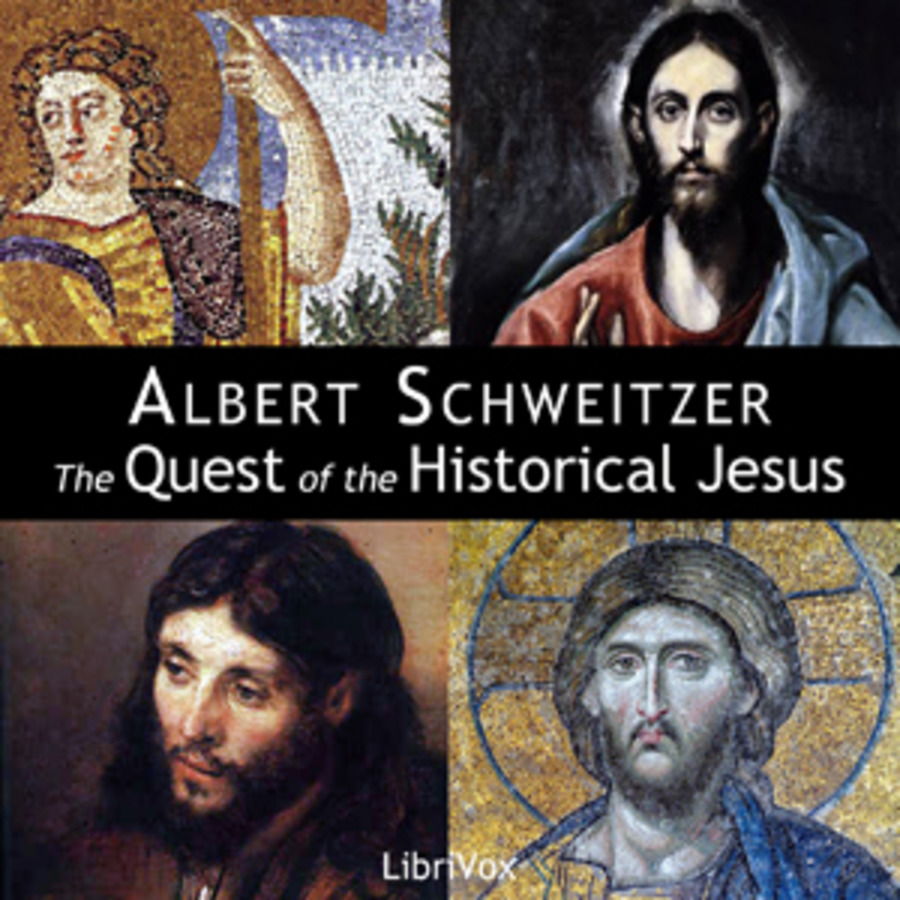

The Promise of Scholarship

Film representations of Jesus, according to Tatum, also have the advantage of appearing “over a hundred years after the commencement of –and has developed alongside – that scholarly and historical preoccupation with the Jesus story known as ‘the quest for the historical Jesus.’” For those not familiar with this term, the “quest for the historical Jesus” refers to a shift in the way scholars have attempted to understand the life and ministry of Jesus. For the majority of Christianity’s 2000-year history, theologians and historians researching Jesus were only able to use the resources available to them, i.e. the Biblical Gospels of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John as well the other books of the New Testament.

This approach presents several problems. For one thing, the Gospels are theological documents and not eyewitness accounts. The earliest Gospel chronologically (Mark) was not written until approximately 40 years after Jesus’ death (almost an entire generation removed from Jesus himself). There are also numerous Gospels that aren’t included in the Bible for one reason or another that sometimes offer conflicting information to the Biblical accounts, further muddying the waters. Perhaps most importantly, most of these theologically-minded scholars were more concerned with articles of faith and belief than pure history to begin with, and drew their conclusions about what Jesus historically did based on these theological precepts. There’s nothing wrong with this, of course, unless your goal is to present an objective image of an historical event instead of a faith-based one. Nevertheless, for hundreds of years the Gospel narratives were the ultimate source of knowledge about Jesus for much of the Christian (and, by extension, the Western) world.

As the Enlightenment came to a close, the traditional practice of interpreting the Bible solely through textual analysis (looking at the Bible only through the lens of the text itself) and “harmonizing” the Gospel narratives (trying to reconcile the differences and contradictions that appear between Gospels to make one, coherent Jesus story) fell out of favor outside religious institutions. Instead, scholars began to apply different research criteria to the Bible, such as reading non-Biblical and non-Christian documents contemporary to the Gospels’ authorship to gain a sense of what life was really like during this time, or comparing the teachings of Jesus to other known religious teachings of the time instead of reading the Gospel in an historical vacuum. In short, this is an attempt to, for lack of a better term, separate the man from the myth, to separate the “Jesus of history” from the “Christ of faith.” The “quest for the historical Jesus,” as it has become known, actually refers to 3 different formal periods (from around 1906, 1953, and 1980, respectively), and is still an ongoing process in contemporary Biblical scholarship. My brief summary here is a gross oversimplification, so I would recommend looking into it further if you’re interested. It’s a fascinating topic for anyone wanting to learn more about one of the most influential individuals in human history.

To come back to Jesus in film, you’ll remember from high school history that the end of the Enlightenment is generally agreed to have come around the end of the eighteenth century (about 1789, with the start of the French Revolution and the beginning of Romanticism), while the first films appeared near the end of the nineteenth century (technically in 1878 with an 11-second “film” of a horse running). So Tatum is correct when he says that portrayals of Jesus in film have benefited from almost a century of Jesus scholarship which opened the door for different interpretations of the Gospel story. Just as scholarly ideas concerning the “flesh-and-blood Jesus” have diversified since the “quest” began in earnest in the eighteenth century, the characterization of Jesus himself in film has also varied wildly. As more literary perspectives and historical insights have become available to filmmakers, Tatum argues, the possibility for more images of Jesus has also increased. In short, film has become an extremely useful tool in the ever-evolving study of Jesus.

And yet, even with these advantages that the film genre offers, filmmakers creating these movies continue to face a number of challenges. Let’s move on to the Problems.