Now that we’ve examined the Promises of Jesus being portrayed in film, let’s look at what Tatum identifies as the Problems for filmmakers.

The Artistic Problem

First, Tatum argues that filmmakers must decide how to approach their project from an artistic perspective (in this case, in the context of cinematography). As we’ve seen, artistic mediums for most of Christianity’s existence were mainly restricted to static forms; “long before there were moving pictures, there were still pictures,” says Tatum. These images have become so familiar for many Christians (and non-Christians) that they frequently embody what and who Jesus IS for their audiences.

If I tell you to picture Jesus, how many of you immediately thought of this picture?

Or how many of you imagine a painting like this one?

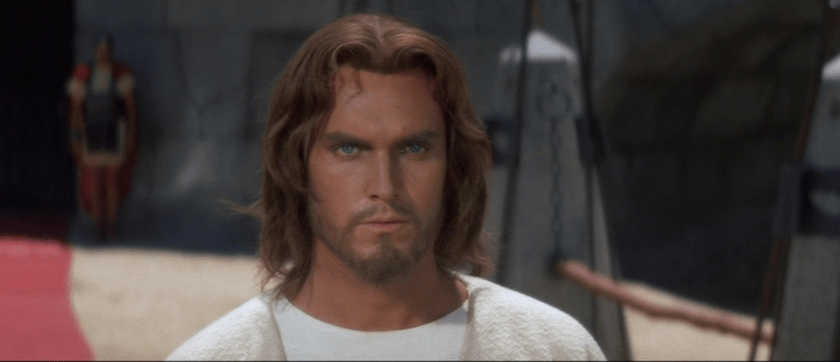

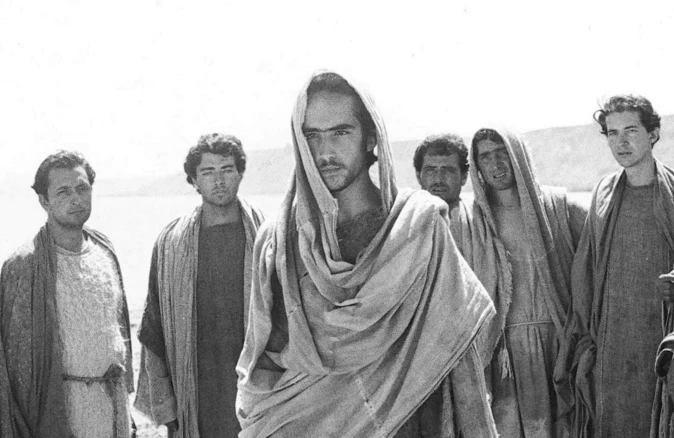

Filmmakers, then, must decide whether or not to attempt to replicate and reinforce these familiar yet static images. Both approaches have been tried with varying results. Let’s take a look, for example, at a clip from Cecil B. DeMille’s silent film The King of Kings (1927). In this familiar scene, Jesus reveals himself to the disciples in the Upper Room after his resurrection. While you’re watching the scene, take note of how Jesus is portrayed: what he says, how he moves, that sort of thing.

So, what is Jesus like in this version? Jesus frequently pauses and poses on screen, bringing to mind the works of the great Renaissance masters and their static portrayal of Jesus. Jesus also only speaks in Biblical quotations (the “red letter words” in some Bibles), never speaking any original dialogue throughout the film. DeMille did this on purpose. He opted to present Jesus in a more traditional representation because he knew that’s what his traditionally-minded audience in 1927 was comfortable with. This was a common practice in the era of silent movies, where actors relied on captions and over-dramatic presentation to compensate for the lack of sound. The fact that movies can incorporate both traditional imagery and capture movement make them a bridge between static art or even stage productions and full-blown motion pictures.

Let’s now contrast this to the film adaptations of the musicals Jesus Christ Superstar (1973) and Godspell (1973).

Both movies feature more active followers and Jesuses (Jesi?) in these and other musical numbers. Compare DeMille’s rigid and “painting-like” Jesus to a Jesus tap-dancing with Judas on top of the World Trade Center or being begged by a crowd to “Touch me, touch me, Jesus!” By this time, of course, the American public had experienced close to 50 years of film, with thousands of stories in varied film genres. Godspell and Superstar notably came after some extremely popular musicals with large choreographed dance numbers such as An American in Paris (1951), West Side Story (1961), and The Sound of Music (1965). Audiences were much more comfortable with serious subjects, like the Passion narrative, being portrayed with comedy or music and dance than audiences in the 1920s were.

Both The King of Kings and the two musicals have remained culturally relevant in part for their adherence to or departure from the traditional representations of Jesus and his story. Even so, they are not universally loved by everyone. Younger generations removed from a time when depictions of Jesus in paintings were the only place they could possibly see him might not have the desire or attention span to sit through a silent movie that relies so heavily on this callback to paintings and stained glass. On the other hand, Christians for whom religion is a more somber and reserved affair might dismiss an aggressively dancing Jesus as inauthentic and not worthy of serious consideration, too contaminated by popular culture to be worthy of worship. The choice of the filmmaker lies in how much he wants to appeal to one or another of these opposites.

The Literary Problem

Secondly, Tatum argues there is a literary issue for filmmakers to address. For the overwhelming majority of Christians, there is one primary source from which to experience Jesus’ story and message: the Gospels as found in the New Testament.

This presents its own problem for filmmakers. All four canonized gospels have different authors and stress different messages to their audiences, making the task of combining them into one “super-narrative” seem very difficult. The Literary Problem, then, mostly deals with the filmmaker’s decision to either tell the story of Jesus from the perspective of only one gospel account (as in The Gospel According to St. Matthew [1966]) or to attempt to combine several or all accounts to encompass as much Jesus as possible (as in just about every other Jesus movie). From a certain perspective, this latter model makes more sense. Think about your favorite stories from the Gospels – Jesus feeding the 5000, raising Lazarus from the dead, the Sermon on the Mount, any of Jesus’ parables, the Nativity story. Most people going to the theater will expect to see some if not all of these famous episodes in a Jesus movie. So the majority of filmmakers opt to adopt this model and cram as many memorable stories into their narrative as possible, in an attempt to appeal to the widest audience possible.

But let’s look at these stories more closely. Do you think the Sermon on the Mount is the culmination of Jesus’ ministry? The authors of Mark, Luke, and John didn’t think so, since this story is only contained in the Gospel according to Mark. Is the resurrection of Lazarus important to you? Only John seems to share that opinion. You’ll probably see Jesus feeding the 5000 in any movie, because that story appears in all four Gospels. But what about the 4000 he feeds later in Matthew and Mark but not Luke or John? Not to mention the many parables that appear in some Gospels and not in others, or that only Matthew and Luke tell the Nativity story (and even then are very different from each other). This isn’t just a throwaway decision by the Gospel writers. Each Gospel has a different message to push, so stories that don’t support their message are thrown out while others that do are kept.

So which is more authentic: to stay true to one Gospel and preserve its author’s message, even if that means leaving out some of Jesus’ most famous stories, or combining every popular story together into one crowd-pleasing, Frankenstein-esque Gospel on the big screen? The filmmaker has to decide.

Even more problematic than this, Tatum argues, is the fact that the Gospels contain “limited information about Jesus and his outer life,” but nothing about “his inner life and his motivation.” Basically, we know what Jesus does (according to the Gospel authors) but not always why he does it. Some Gospels even go out of their way to keep Jesus’ motivations secret from the reader. Naturally, this poses an artistic and theological problem for the director attempting to present a Jesus with whom the audience will sympathize. Either the director will choose to take liberties characterizing Jesus as they see him, potentially resulting in alienating audience members who will argue that such liberties are not theologically sound; or the movie will feature a Jesus who is theologically inoffensive but who is dramatically boring. Think back to The King of Kings. Remember that Jesus only speaks in the “red letter words” found in the Bible that ostensibly quote Jesus. DeMille intentionally decides to play it safe with his Jesus and make him completely Biblical, without adding any characterization of his own.

On the extreme other hand, Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) has become infamous for its almost complete departure from the traditional Christological expectations of its audience. In this film, Jesus, played by Willem Dafoe, is very human – for many Christian critics, too human. We’ll examine this film more closely when we discuss Tatum’s Theological Problem in the next section.

The closest that other, traditional Jesus films usually come to tackling Jesus’ humanity Jesus’ usually comes during the scene in the garden of Gethsemane before his execution. Jesus has a moment of doubt and asks God to spare him from the coming pain he must endure. Jesus Christ Superstar‘s song “Gethsemane” is a great portrayal of this. For the most part, however, filmmakers tend to play it safe with their presentation of Jesus and stick to the source material. While this approach might be considered boring, it ironically leads to more interesting characterization of other important players in the Passion narrative who act as foils for a flat Jesus. As the betrayer of Jesus, Judas is a natural choice to be everything Jesus is not. Where Jesus may be calm, collected, and certain of his future, Judas is anxious, frustrated, and more prone to lash out in fits of emotion. So Judas is therefore more relatable to the audience, and frequently becomes a more interesting character in many films. This even inspired someone to make Judas the subject of his own made-for-TV movie, proving that audiences will even root for the villain if the story is good.

Now let’s discuss Tatum’s other two Problems: the Historical and the Theological.