The Historical Problem

Third, Tatum argues filmmakers must deal with the historical aspect of Jesus. How historical does the director want his Jesus to be? Since the first films about Jesus of Nazareth were made, directors have attempted to portray Jesus and his historical surroundings as accurately as possible to preserve the sanctity of the story. At the same time, however, filmmakers and audiences both want a good story, even if this means embellishing or leaving out certain historical elements. So films inevitably feature hordes of Palestinian Jews “barefoot and bathrobed” following Jesus through the desert, with an occasional smattering of Roman soldiers in full armor watching from afar and richly-dressed Temple priests sneering behind Jesus’ back.

Beyond simple costume design, however, lies the distinction which must be made between what Tatum calls the “Jesus of history” and the “Christ of faith.” What do we know about the historical rabbi from Nazareth who was killed by the Romans in the first century C.E., and how is this different from what 2000 years of tradition has added to his story? Much of this distinction comes out of advances in scholarship to separate the two figures within the context of the gospel accounts, part of the aforementioned Quest for the Historical Jesus.

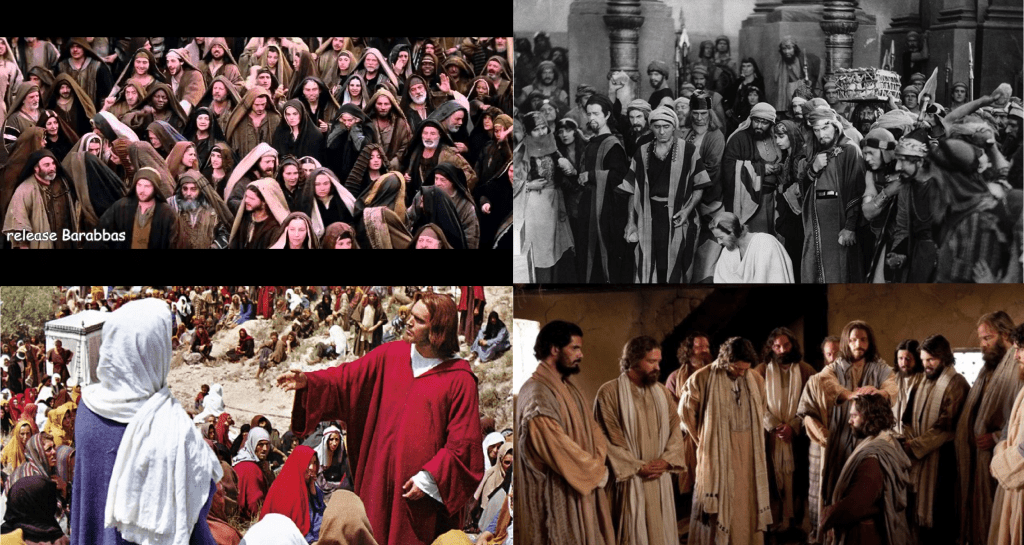

In film specifically, Tatum argues that this distinction is characterized in the choice made by directors in who they portray as Jesus’ killers. For much of early and medieval Christian history (and unfortunately even into modern times), it was accepted as truth that the Jews of the first century were the ones who killed Jesus, the incarnation of God on Earth. As abhorrent as this sounds to us, it’s not as if this is not without Biblical precedent. Christian theologians mostly pulled from one verse in Matthew where, after condemning Jesus to crucifixion, a Jewish crowd cries “His blood be on us and on our children!” These religious thinkers used this to make all Jews liable for the death of their savior and therefore the recipients of eternal damnation, and carried out horrific acts on Jews with this justification. Luckily, more enlightened ages of history slowly but surely brought about more enlightened Christian scholarship, another advantage to the Quest for the Historical Jesus, and despite certain infamous exceptions, scholarly and Christian views on this subject have thankfully changed. Another fascinating topic for those interested, the blame for Christ’s death has properly been placed on the Romans for executing a seditionist against the State with crucifixion and not a religious criminal (who would have been stoned to death). Unfortunately, there are no living Romans left to blame, so Jews have historically received this hate based primarily on this one passage.

Early in the history of Jesus films, issues of anti-Semitism and avoiding on-screen condemnations of Jews as “Christ-killers” were very much at the forefront of filmmakers’ minds. However, even though the intent may have been good, the policy was not always well-executed. The King of King‘s director Cecil B. DeMille, for example, was reportedly shocked when Jewish authorities decried his film “for its tendency to revive anti-Jewish religious prejudice.” While his response may have been more than a little narrow-minded, he seemed genuinely offended that Jews would accuse his movie of being threatening to them.

In 2004, a similar film reignited the issue. Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004) was condemned by critics as especially promoting anti-Semitism in its portrayal of Jews as the main actors of violence against Jesus. Jewish critics such as Robert Jacobs, the head of the Pacific Northwest Anti-Defamation League, went so far as to call the film something that “might reverse the past 40 years of increasing interfaith dialogue or result in misunderstandings that could harm Jews both here in the United States and overseas” in its portrayal of “the High Priests and the Jews of Jerusalem as horribly vicious, brutal and inhuman.” I would have to agree; in one scene the Jewish children’s faces warp and distort to demonic extremes while Satan can be glimpsed through the crowd overseeing the ordeal. Whether the intent of Gibson was to portray the children as demonic because of their Jewishness or as simply demonic, I can’t say. Nevertheless, it seems this and other parts of the film did not sit well with some Jewish leaders.

But I would be remiss to continue without mentioning the incredible amount to detail and historical accuracy that The Passion of the Christ also pays to everything it can, namely its dialogue. Instead of English, every character speaks in a language that would have been spoken in 1st-century Palestine. Jesus and his followers speak in Aramaic, Hebrew abounds in prayers (although the Jewish priests also speak in Hebrew, which is a little weird since Hebrew would have been reserved for prayers as a holy language), and Romans speak in Latin. This is a massive undertaking for everyone involved, so I believe in giving credit where credit is due for going as far as possible to recapture some aspect of historical authenticity. It even impressed Pope John Paul II so much that his verdict was simply “It is as it was.” Given the intent of the film and its subject matter, perhaps this is the only endorsement that really matters for a Jesus film director.

Then again, this is the same movie where Jesus is responsible for inventing the modern dining room table and chairs, which really rocks how I had imagined “it was” back then.

So maybe we haven’t made the perfect Jesus film yet.

The Theological Problem

Finally, Tatum acknowledges the theological issues present in any project attempting to capture the life and meaning of Jesus Christ. Filmmakers face a challenge familiar to all Christian artists, past and present: that any physical representation of the Son of God as a human man will inevitably ruffle someone’s theological feathers. Or, as Tatum succinctly summarizes, “What does a man who is also God look like?” Tatum goes on to explain:

“Because of Jesus’ place in culture as well as in church, most persons who see Jesus on the screen not only know what he looks like, and know his story, but they also have a personal stake in him and his story. Jesus’ story is, in some sense, everyone’s story. However, the Christian church or churches and their Christian constituents – in particular – view Jesus as belonging to them. Jesus is the Christ. He is their Jesus Christ.”

In the face of such a seemingly insurmountable obstacle, the famous words of the medieval poet John Lydgate come to mind: “You can please some of the people all of the time, you can please all of the people some of the time, but you can’t please all of the people all of the time.” It would be tempting to find solace in this idea and move on. In practice, however, this is hardly an adequate response. The Christian faith has been split and blood has been continuously shed over such disagreements about the degree to which Jesus was human and/or divine, even to the present day, and movies are no exception.

In addition, Tatum points out that theological issues can go beyond simply disagreeing with a representation of the Incarnation, but can extend to any perceived departure from the Biblical (i.e., infallible and inerrant) text as being an irreconcilable challenge to their faith. If you take your interpretation of the Bible and the Gospel story as the direct word of God, for instance, and someone makes a movie with a version of Jesus that doesn’t fit that view, they might consider it an affront to them personally instead of a simple difference of opinion.

Martin Scorsese’s Last Temptation of Christ (1988) is perhaps the most infamous example of a serious and mainstream challenge to the traditional representation of Jesus. Based on a 1955 novel of the same name by Greek author Nikos Kazantzakis, the movie features a Jesus that is very human. While Jesus is still without sin, he is subject to fear, doubt, depression, reluctance, and lust. He struggles with his humanity and his role as God’s instrument for the salvation of humanity. Because of this, many Christians were incensed with Scorsese’s depiction of Jesus (portrayed by Willem Dafoe) as a man who was much more human than they were comfortable with. Film critic Harlan Jacobson articulated many people’s frustrations:

In the rush to spill so much passion over Martin Scorsese’s divine inquiries in The Last Temptation of Christ, the first question Christ grapples with in both Nikos Kazantzakis’ novel and the film has simply disappeared: not was he man or God, but was he nuts?

Here, in this clip from near the beginning of the film, we see Jesus express his doubts as to his messiahship. It’s an interesting approach to the study of Christ, and a different angle than I’ve seen presented in any of the other Jesus movies I have seen. However, the very idea of this kind of Jesus is one that offended many. but not one that is especially palatable to the faithful at large. Even if you are not especially religious, you can probably understand why devout Christians would be so offended by this version of Jesus.

But by outright rejecting the film for what they perceived to be attacks on their faith, many Christians miss out on encountering a fascinating (if at times intense) portrayal of the story of Jesus. Instead of seeing the film as an opportunity to explore Jesus’ humanity as an unfamiliar facet of the complex Gospel narrative, protesters decided to immediately reject it as blasphemous. Such material was therefore not worth engaging with except to boycott it. These protests were carried out with typical Christian calmness and collected-ness, such as when one protestor dressed as the head of MCA Studios outside the president’s house and pretended to drive nails into Jesus’ hands.

On the other hand, professional critics of the time pretty unanimously loved this film. Perhaps most pertinent to our discussion, Gene Siskel remarked:

Dafoe manages to draw us into the mystery, anguish and joy of the holy life. This is anything but another one of those boring biblical costume epics. There is genuine challenge and hope in this movie.

And Roger Ebert added:

[Scorsese and screenwriter Paul Schrader] paid Christ the compliment of taking him and his message seriously, and they have made a film that does not turn him into a garish, emasculated image from a religious postcard. Here he is flesh and blood, struggling, questioning, asking himself and his father which is the right way, and finally, after great suffering, earning the right to say, on the cross, ‘It is accomplished.’

Christian critics tended to feel differently, but they always seem to be in the minority of film critics.

Ironically, the first thing these protesters would have seen had they viewed the film is the message “This film is not based on the Gospels, but upon the fictional exploration of the eternal spiritual conflict” even before the opening credits. I would personally encourage everyone to view this film at least once, if for no other reason than as an example of how the Quest for the Historical Jesus has influenced and inspired such different ways of interpreting such a nuanced story as that of Jesus.

It’s also worthwhile to note that Mel Gibson faced similar scrutiny in Passion of the Christ for the relative lack of emphasis he placed on the Resurrection, and therefore presenting a film with an incomplete theology that emphasized the suffering and the death of Jesus. Given the other issues levied against this movie as outlined above, however, debating this theological difference of opinion might not have been their most immediate concern.

So we’ve seen how difficult it can be to make a film about Jesus that makes everyone happy. This seems to support my original idea that Jesus is the nail in the coffin (pun intended) for these movies. But before we draw our final conclusions, there is another aspect of Christian cinema we need to discuss: message films.