So as we have seen, the filmmaker who attempts to tell the story of Jesus has more to deal with than other directors whose films remain in the realm of the secular. Even films that feature overt “Christ-figures” are usually able to avoid angering religious communities because they don’t deal with Christ directly, no matter how ham-fisted the Christ metaphor may be inserted into the story. The latter three aspects of Tatum’s challenge, as we’ve seen, frequently result in a more static and less fluid Jesus reminiscent of the paintings from which they gain their inspiration. This, in turn, leads to even remotely-historical Jesus films becoming message films.

Message Films

But what is a “message film”?

As their name suggests, the primary purpose of message films is to push a message or moral to their audience, in this case a Christian one. Any film that directly features Christian themes and material could conceivably be considered to be a message film. In fact, searching for lists online of the top Christian films yields many familiar results, such as The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, It’s a Wonderful Life, and the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

These well-known examples, however, are more films with Christian elements or allegory material in them, not Christian films per se. When I use the term “message film,” I’m really talking about a more specific subgenre of Christian cinema. Generally, message films tend to be made by openly-expressing Christian directors and studios, and are targeted specifically toward Christian audiences. They don’t usually have as large a budget or production value, and are not as well-received by non-Christian critics (although it could be argued that filmmakers whose intent is to spread a Christian message may not care as much what non-Christian critics think).

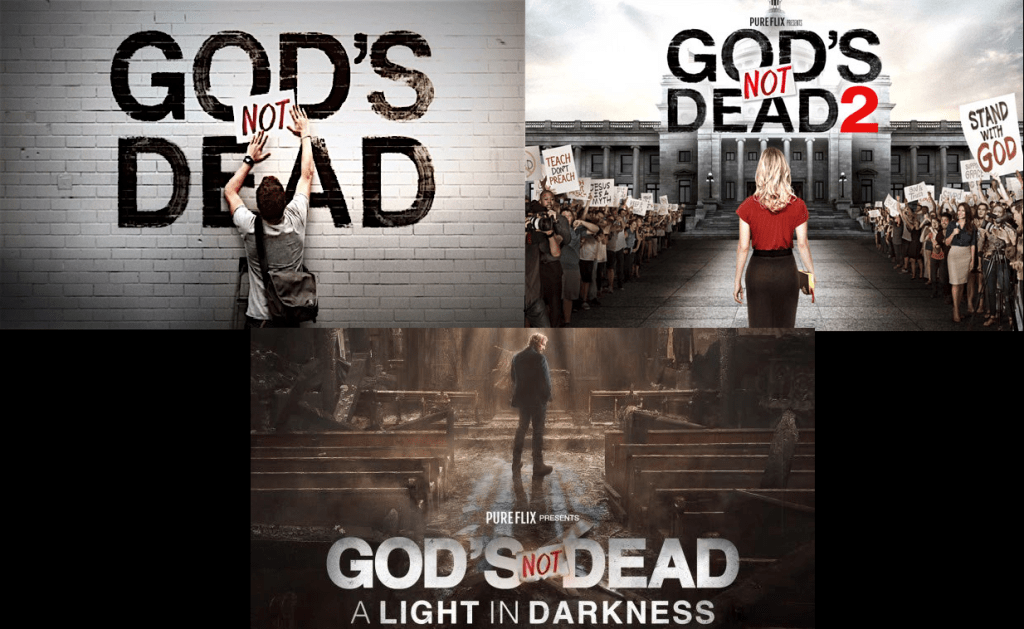

One series of popular message films even non-Christian audiences are probably familiar with is the God’s Not Dead trilogy (God’s Not Dead, God’s Not Dead 2, and God’s Not Dead: A Light in the Darkness). These films make use of simultaneous narratives to tell several stories at once that eventually come together at the end and share overlapping Christian themes. As we’ll see, they certainly fit the stereotype of modern Christian cinema as overly-saccharine and low artistic standards.

In order to show you what I mean, I’d like to summarize the first film in the series, God’s Not Dead. This will be a little lengthy, but I really want to emphasize the ridiculousness of these types of movies, so I think it’s worth it.

In the first film, the main story focuses on the conflict between Josh Wheaton, a college freshmen whose identity is “being a Christian,” and his philosophy professor Jeffrey Radisson, a really nasty atheist. I’m emphasizing their religious views because that is their most important characteristic in this movie. It makes sense to do so, seeing as they are stand-ins for Christianity and the secular world, respectively, but I also want to emphasize the heavy-handedness of the film. The movie can’t go five minutes without using these religious identities to beat the audience over the head with a “Christian good, atheist bad” moralizing.

Wheaton wants to be a good Christian and also a good student, but realizes this is not possible at his college when he goes into his first philosophy lecture and is told to sign a paper which states “God is dead.” This, he is told by the evil Professor Radisson, will allow the students to learn something worthwhile by letting go of any attachment to “pre-scientific superstitions” about God. Wheaton decides he cannot sign this, as it would betray his Christian faith. Radisson then challenges his freshmen college student to debate him in an attempt to prove the existence of God to his fellow classmates, and states that if Wheaton fails to convince the students Radisson will fail him. The over-the-top nature of this premise shows the narrow and good vs evil worldview of the film’s writers. The remainder of the film shows both their classroom debates retreading centuries of Christian “proofs” as well as their confrontations outside class where Radisson reacts to Wheaton’s faith as if a roving band of Christians shot his dog as a boy. Seriously, the animosity some of their confrontations is baffling but not particularly shocking in a film of this quality, as we shall see.

God’s Not Dead also follows several other Christian or soon-to-be Christian characters as they navigate a world hostile to the largest religion on the planet. Professor Radisson is dating a Christian woman named Mina, whom he constantly belittles in front of his professorial colleagues (who are all atheists, by the way, as is everyone in academia). Mina’s brother Mark, a successful businessman/atheist, both refuses to visit their elderly mother with dementia and decides to dump his girlfriend Amy when she tells him she has cancer. Amy is a left-wing blogger (but NOT a Christian) who writes blogs that attack Duck Dynasty, of all things. This is important to the plot because it allows one of the Ducks, Willie Robertson, to make a cameo in the movie. A Chinese exchange student, Martin, is inspired by Josh’s debates and writes his businessman father that he wants to become a Christian. A local preacher, Roland, experiences all sorts of what can only be described as mundane inconveniences compared to being disowned by one’s family, with his optimistic friend always in the background to chime in with a “God is good!” and a smile. There’s even a short subplot where a Muslim girl, Ayisha, secretly listens to Christian podcasts on her iPod in order to hide her secret conversion from her very religious father. When her father discovers her dark secret, he literally throws her out of the house onto the street to fend for herself.

In the end, everything works out as you’d expect. Josh wins over his classmates in the final debate, and Martin triumphantly declares “God’s NOT dead!” as the entire class follows him out of the lecture hall. Mina finally stands up for herself and dumps Radisson because he’s an ass, although the movie is clear in pointing out he’s only an ass BECAUSE he’s a militant atheist. Amy the blogger converts to Christianity and is cured of her cancer as a result. Mark finally visits his mother to taunt her for her faith not curing her dementia, only for her to tell her son that his wealth comes from Satan (although he still gets to keep his wealth, so points docked from the writers for a missed opportunity). Martin is taken in by Pastor Roland to work at his church, and Ayisha is taken in by the Christian community as well. A Christian band called The Newsboys hears about Josh’s debate, and while throwing a concert Willie Robertson encourages everyone to text everyone they know that “God’s not dead” to share the good news. The good guys get to have their party and the bad guys get their comeuppance.

But the worst fate is reserved for Professor Radisson. It turns out that Jesus inherited some of his dad’s Old Testament-style temperament, and Radisson learns this the hard way. It turns out Radisson hates Christianity so much because his mother died when he was young, no matter how hard he prayed to God to save her. After he loses his debate with Josh, Radisson finds a letter from his mother that moves him enough to try to reconcile with Mina, who is at the concert. But on the way to the venue, he is hit by a car (who doesn’t even slow down and drives away) and converts to Christianity with Pastor Roland in the rain before he dies in the street like a dog. It’s so heavy-handed and moralizing that it’s laughable instead of the powerful scene the filmmakers surely intended it to be. Even C.S. Lewis at least used allegory to get his message across.

The sequel to this film, God’s Not Dead 2, continues this trend to satisfy its audience of believers without worrying about the what rest of society thinks (unless they can convert them). This time, the setting is a rural high school where Melissa Joan Hart cashes a check as a history teacher who, when asked a question about influential figures in history, literally says that Jesus’ teachings have had a huge impact on history and is immediately brought up on legal charges for advocating for religion in public schools. She goes to court, falls in love with her lawyer who himself eschews his atheist lawyer job to become a Christian (because those are mutually exclusive), she (and by extension, God) is found innocent and everyone walks out of the courthouse to proclaim that God is still not dead. The villain (who is a lawyer, they’re all lawyers) is even more over-the-top evil in this movie, an Emperor Palpatine to the previous movie’s Darth Vader. It’s almost as if the producers of the first film had a bad experience with lawyers in the past.

But this heavy-handed is exactly what message films like God’s Not Dead are all about. They are so concerned with delivering a safe and theologically-satisfying message to their target audience that important aspects of film like plausibility or quality acting are pushed aside. Seriously, I’ve seen better acting on daytime TV.

To put it another way from this interesting article from Vox:

So a Christian movie is a Christian movie if it states forthrightly the beliefs of the filmmaker. The communication of those beliefs is the most important thing. Everything else — including most categories of filmmaking artistry that, say, critics would primarily care about — is secondary, helpful only insofar as it helps the filmmaker win more non-Christians to the faith. The goal, in other words, isn’t to make a movie. The movie is only the vehicle for achieving the goal. The real goal is engaging and converting secular culture.

An older but popular message film, The Jesus Film (1979), is similarly preoccupied with “getting the message out there” and converting as many people as quickly as possible. These films endear themselves to their audience because of their message, and no Latin soap opera-quality of acting will convince them otherwise. When I reached this section of our discussion when I gave this as a lecture, I was told to my face that I was wrong about how dumb these movies are. They can be very powerful to their viewers.

I haven’t had the pleasure of seeing the third installment, A Light in the Darkness, but when I do, I’ll be sure to enjoy a tasty faith–themed cocktail to help me experience it to the fullest extent.

So is this the answer to our original question “Why do Jesus movies suck?” Because any movie that is overtly Christian is inevitably going to worry more about its message than its quality, and what is more Christian than a movie about Jesus himself? In our final segment, we’ll try to find an answer.