Ben-Hur (2016): Ruining a classic

So now that we know what “message films” are and their purpose, we can come back to where we started — with Jesus and Ben-Hur.

In 2016, a new version of Ben-Hur was released by Paramount Pictures. I actually paid to see this remake in theaters, not because I generally have any desire to see a remakes of anything but because I liked the 1959 version so much I was curious as to how the filmmakers could possibly try to remake this movie. I went in with low expectations, and I was not disappointed. There are a number of elements pertinent to our original question “Why do Jesus Movies Suck?”

The 2016 version of Ben-Hur shared much with the 1959 version. Prince Judah is betrayed by his childhood friend Messala and sold into slavery, Judah survives a great naval battle and vows revenge on Messala, there’s a big chariot race, and also Jesus is there. But there are notable differences in the newer version that, in my opinion, spit in the face of the original.

The Ending

The most egregious of these changes involves the ending. In the 1959 version, after the great chariot race between Judah and Messala, Messala not only loses by not coming in first place but is also trampled by his horses and mortally wounded. He only lives for a short while longer by clinging to his hatred for Judah, and dies cursing Judah’s name. Judah is also consumed by hatred of all Romans after this, and it is only through witnessing the Crucifixion that he is able to let go and move on with his life in a constructive way. Messala’s death is used as an example of how NOT to live.

The 2016 ending is completely different. Messala still loses the race, but only loses a leg instead of his life. When Judah visits him later in the film, a bedridden Messala is ready to kill him. Judah, however, has already embraced Jesus’ “turn the other cheek” philosophy after seeing Jesus die on the Cross and forgives Messala for everything he has done to him and his family. Messala, who is humbled by this act of forgiveness, decides to forgive Judah for beating him in the chariot race. As Judah and his family decide to leave Jerusalem, Messala is invited to join them on their journey, and even reconciles with his childhood sweetheart Tirzah, Judah’s sister. Who doesn’t seem to mind that Messala is the one who locked her and her mother up for years and caused her to contract leprosy and almost die. Everyone forgives everyone for every horrible thing they’ve ever done to each other and they ride off into the sunset together to presumably become Christians. It’s heartwarming and saccharine, and I hate it.

Not only does this ending run contrary to the meaningful ending of the 1959 version, it also completely contradicts everything that has happened in the film up to this point. 1959’s Judah gets his revenge but finds it leaves him empty and more full of hate than before, and after being spiritually transformed by Jesus’ sacrifice learns not to let hatred consume him like it did Messala. 2016’s Judah does maim Messala, but his victory is more subdued because he’s able to forgive Messala for his evil deeds towards him and his family. The battle between good and evil has become integral to Christian theology. If Messala’s evil is not wholly punished, as it was in 1959, then what is this newer version’s message? Where is the moral admonishment to stay away from evil? It would seem the director himself has the answer:

“It’s a very contemporary movie, the script we are making now, very relatable,” he says. “It’s not about revenge, as it was in the 1959 movie, but forgiveness. Today, in our world, where we’re all fighting, people and countries, I think that learning how to forgive each other is really important. It’s the only way we can survive.”

In trying to update a near-perfect classic for a modern evangelical Christian audience of America, the filmmakers have castrated the powerful message of the film they are attempting to emulate. And so they have, without hyperbole, given us the stupidest and most asinine ending I have ever seen in a movie ever. In short, 1959’s Ben-Hur is a classic; 2016’s Ben-Hur is a message film.

Marketing

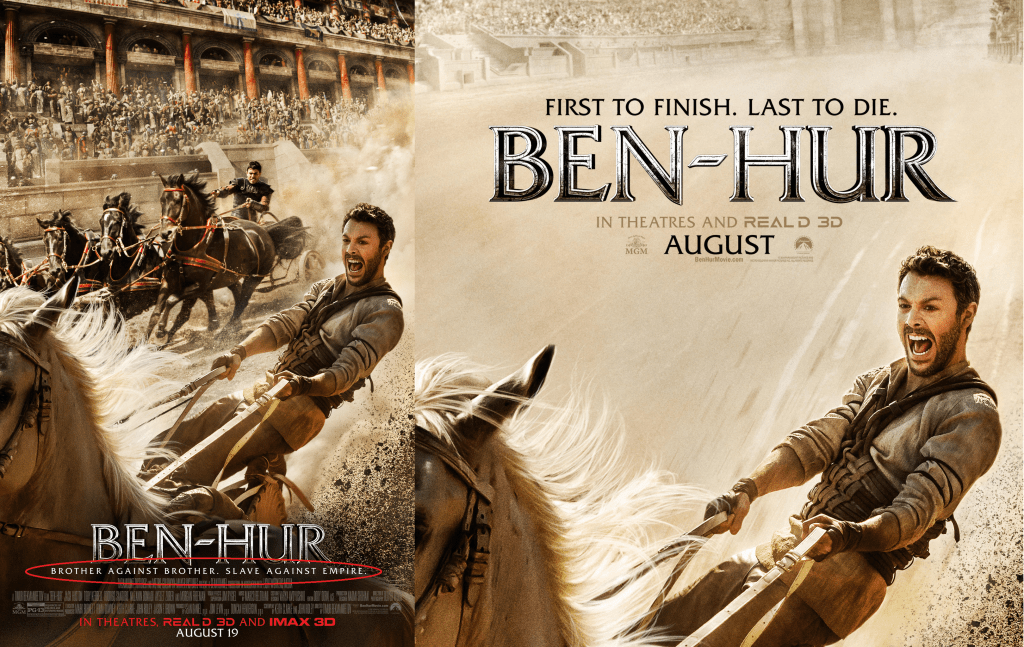

This is even more apparent when you look at the difference in the marketing for the film. On the one hand, you have promotional material which promises to recall the glory of the 1959 version with scenes from the new and improved chariot race. The taglines for this side of the marketing are things like “Brother Against Brother. Slave Against Empire.” or “First to Finish. Last to Die.” Obviously, these posters and taglines are meant to drawn young men into the theater to see an epic action movie, reminiscent of Gladiator (2000) or Spartacus (1960). And to be fair, if I were a Hollywood executive, these are the posters I would use to lure that audience in, too.

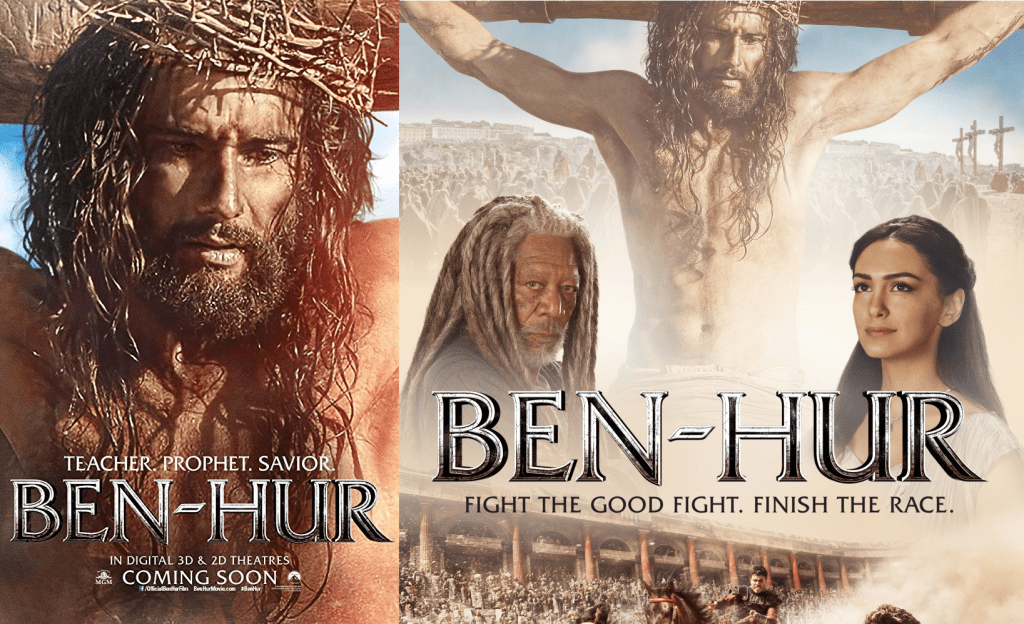

But there is another side of the marketing targeting a very different audience, i.e. an explicitly Christian one. These ads focus more on Jesus himself, usually on the Cross (arguably the most important event in Christianity). Their taglines are much more benign, such as “Teacher. Prophet. Savior.” or ” Fight the Good Fight. Finish the Race.” According to these posters, Jesus IS the focus of the movie, and Judah is merely the vehicle for Jesus’ message. This seems like a strange marketing strategy to me, considering that a) audience members who are more religious generally tend to be older, and are probably very familiar with the well-beloved 1959 version of the film, and b) are probably fond enough of the earlier version to not see the necessity for a remake.

There are even examples where the two styles blend, such as this example where the “action” material is placed under the “religious” material, symbolically asserting that the latter message is superior to the former’s spectacle. (Spoiler: this is exactly what is done in the film and for the same reason.)

Whatever the rationale, the stark difference in marketing slogans clearly shows the two audiences this film is targeting.

Jesus

Aside from this infuriatingly altered ending and the marketing, there is one other difference between the films important for us, and that is how they choose to portray Jesus.

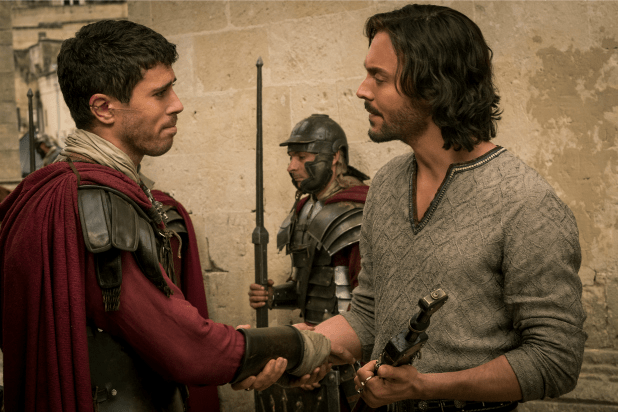

Jesus appears to Judah Ben-Hur at two crucial points in both films: once, when Judah is being taken by Roman soldiers to a life as a galley slave in the Roman navy, Jesus offers a famished Judah water; and later, at Jesus’ crucifixion, Judah returns the favor by offering water to Jesus as he stumbles carrying his own cross, returning the favor. Through the example of Jesus, Judah is transformed from one who vengefully wields the sword to one committed to the way of love.

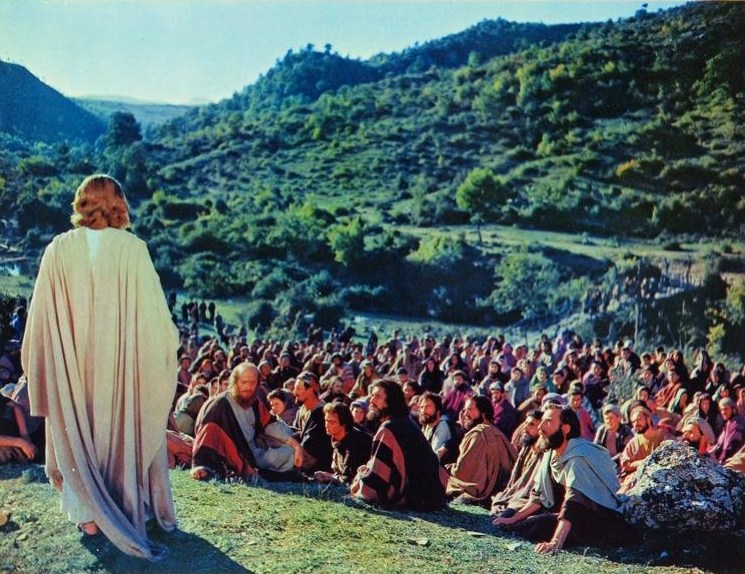

While the original Ben-Hur does feature Jesus as a story-influencing character, he is to the periphery of the plot for the majority of the film. We only ever see Jesus’ hands or the back of his head, or another character’s reaction to seeing Jesus’ face. Jesus also never speaks, so we don’t hear him voice any opinions at all.

The 2016 Jesus, on the other hand, is very present and vocal in his version of Ben-Hur. Even when Judah is still living as a privileged prince, Jesus lectures Judah and his girlfriend Esther about not being socially conscious about the plight of the Jews under the Romans. Esther, herself an important influence on Judah, is part of Jesus’ entourage, waving palm branches as he enters the city and attempting to defend him when he is arrested in Gethsemane. The trial, torture, and execution of Jesus is played out not in the expression of those who witness it but by seeing Jesus’ own expressions. We see Jesus straight on, and while we are able to see characters’ reactions to his words, by that point we have already reacted to his ideas ourselves. This presentation of Jesus leaves nothing to the imagination.

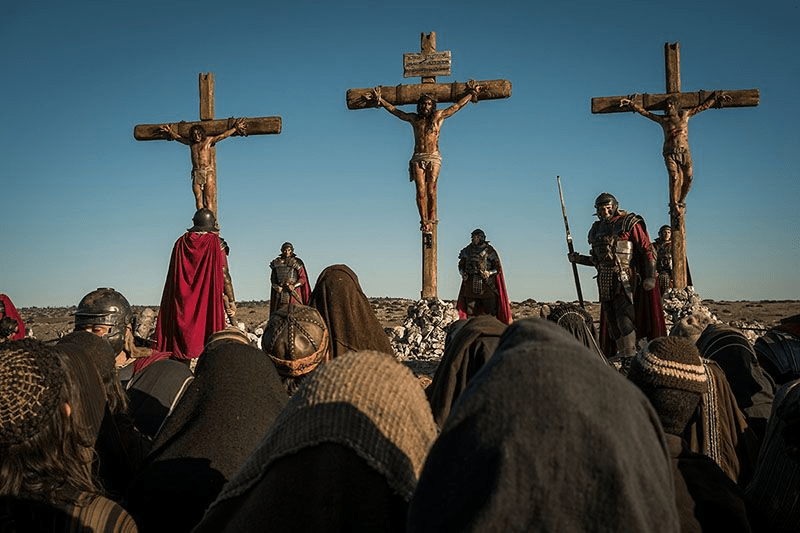

This major change is present throughout the movie, including how the Crucifixion is portrayed.

Conclusion

So what does this difference matter? Remember Tatum’s Promises and Problems for the filmmaker making a Jesus movie. Whenever a director decides to portray Jesus, they are inevitably going to make someone angry because their vision of Jesus is just that — the director’s personal version. The director of 2016’s Ben-Hur, Timur Bekmambetov, chose to portray Jesus the way he views him, as a forgiving and socially-conscious savior. In 1959, director William Wyler chose a very different method of approaching Jesus, from a detached viewpoint. By offering fewer specific details for audience members to pick apart and criticize, it strengthens a positive portrayal of Jesus for the audience. In this case, less seems to be more.

Maybe even more importantly, the thematic material that the 1959 Christ stresses (putting down the sword and committing to love) is nevertheless powerful and meaningful in spite of a lack of an overt Jesus “preaching at” the audience. The 2016 version throws this subtlety out the window, and as a result falls victim (like so many Jesus films before it) to putting the director’s personality into a character meant to speak to the individual audience members. In my view, 1959’s way is the superior model, and one I think is proved by the continued success of Ben-Hur with Christians across denominational lines and with critics alike.

Or, to quote Tatum:

To what extent is this film about Jesus not only cinematically interesting, but literarily sensitive to the gospel sources, historically probable, and theologically satisfying?

This certainly no easy task, and as we have seen is one that is seldom met by filmmakers.

So, to sum up:

- Just because Jesus is in a film doesn’t mean it sucks.

- The further away Jesus is from the focus of the film, the less pressure is on the filmmaker meet audience’s expectations of Jesus.

- This generally results in a more widely well-received movie.

In the end, my “Jesus in America” class turned out to be more thought-provoking than I had initially expected. I learned to have a new appreciation for the obstacles filmmakers face when trying to create an enjoyable experience, especially when tackling such a sensitive subject. And I watched a whole bunch of Jesuses traipsing around Hollywood lots and Middle-Eastern deserts. Maybe most importantly, I passed the class and felt like I was able to at least somewhat justify those grad school student loans. And isn’t that really the greatest miracle of all?

Bonus – Jesus on the Cutting Room Floor

In my search for the cinematic Jesus and why his movies bored me so, I came across many different kinds of films dealing with the life and death of the Lord. As the last hundred or so years of cinema have allowed directors to create entirely new genres of film, Jesus has become a figure in more and more varied ways. Some of them are just too good to not mention.

The Miracle Maker (1999)

I actually remember seeing this movie on the wall of my local Blockbuster back in the day. Unfortunately for Jesus, my sister and I were more interested in renting The Princess and the Goblin for approximately the 400th time than watching a dead-eyed clay Jesus stop-motion his way to the cross and into our hearts. I recently read someone compare this movie to an episode of Robot Chicken, and honestly that’s exactly what this reminds me of.

Jesus Christ Vampire Hunter (2001)

According to this film’s sparse Wikipedia page, this film “deals with Jesus’ modern-day struggle to protect the lesbians of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, from vampires with the help of Mexican wrestler El Santo.” I prefer this online review:

This cult favorite is so crammed to the brim with mixed genres that its mere stench lifts the lid off the jar and overflows with oozing mediocrity. It’s a kung-fu movie. It’s a splatterfilm. It’s a Mexican wrestling film. It’s a musical! It’s a Jesus film with multiple personality disorder. And all of them are batshit insane.

Personally, I can’t wait to make myself a King Solomon’s Cooler and see what is going on with this one.

Ultrachrist! (2003)

Jesus returns to present-day New York City, but has trouble connecting with the superhero-obsessed youth of today. In order to get their attention, he dons a cape and puts his underwear on the outside to become Ultrachrist, fighter of sin. His father, however, does not approve, and Jesus must find a way to spread his message and save the day. Superheroes have always been popular, but I do think it’s funny that this movie came out in 2003, five years before Iron Man would start printing money for Marvel and continue to do so through today. Truly, this movie was ahead of its time.

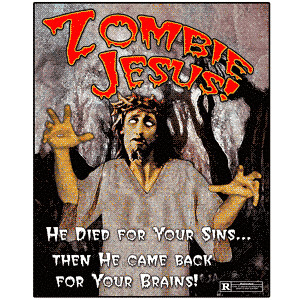

Zombie Jesus! (2007)

I think the tagline says it all.

Fist of Jesus (2012)

I really like the idea behind this Spanish short film. We open to a familiar scene where Jesus is attempting to resurrect the deceased Lazarus from the dead. Seeing as this is first resurrection, however, he botches it, and Lazarus instead come back as a zombie and immediately starts infecting Judeans and Romans alike. Jesus must join forces with an unlikely ally to unleash a blood-splattered hurricane of holy fury to rid the Holy Land of the undead menace. I’m not a huge fan of how bloody it is, but as a short film its lasts just long enough to not overstay its welcome. It’s worth at least one viewing.