It certainly has been a while since the last time we visited a movie from before the MCU, but with everything going on with our global pandemic and cultural unrest in the US, I hope I can be forgiven for procrastinating a little. Hopefully taking some time to look at and poke some fun at old films will be an enjoyable distraction from 2020.

So now we come to the movie that started me down this path in the first place. If you’ll recall, the reason I wanted to rewatch these superhero movies released before Iron Man and The Dark Knight (both from 2008) was to see the tonal difference between these older movies and Marvel’s current catalog. It seems to me that there is something distinctive about the Marvel “style” of these movies that allows us to group them all together in terms of tone and structure (all of them being made by one studio is definitely a factor) and that separates them from earlier films of the superhero genre. Fantastic Four just happened to be the first film that came to mind. As I said at the outset in my first post: the one time I caught FF on TV in the middle of the day, it was entertaining and fine. Not bad, but not great either – fine.

And yet, everywhere I look, people seem to be personally offended in how much they don’t like this movie. It tends to be much more polarizing and talked about than some of the other films in our series, and seems like it has been since its release. Take this review from back in 2005 from Roger Ebert, no less:

The story involves Dr. Doom’s plot to … but perhaps we need not concern ourselves with the plot of the movie, since it is undermined at every moment by the unwieldy need to involve a screenful of characters, who, despite the most astonishing powers, have not been made exciting or even interesting… And the really good superhero movies, like “Superman,” “SpiderMan 2” and “Batman Begins,” leave “Fantastic Four” so far behind that the movie should almost be ashamed to show itself in the same theaters.

I mean, I didn’t think it was as good as any of those other movies either, Roger, but “ashamed to show itself”? That seems a little harsh to me. Then again, this is coming from the man who originally panned Alien , so perhaps even the greats aren’t right all the time.

But it appears I’m in the minority about the movie, as this review from earlier this year seems to suggest:

1994’s Fantastic Four might have been cheap and kind of stupid, but at least it was enjoyably dumb. That is a movie where you can get a good laugh, however unintentional. In the 2005 movie, for all the effort that was supposedly put into it, it really left the Fantastic Four looking, well, flaccid.

Now, as someone who actually has viewed the 1994 Fantastic Four in its entirety, I can tell you that while I do agree that it is “enjoyably dumb,” it is not better than the 2005 version by any metric.

As an aside, the story behind the unreleased 1994 film is such a bizarre and interesting tale that it deserves its own entry. You can actually watch the entire thing on YouTube, if you have the time and the desire (and who doesn’t right now?). For now, though, take a few minutes to the opening credits’ score that’s surprisingly good for the movie it’s attached to.

Obviously the 2005 Fantastic Four movie isn’t meant to simply be ridiculed, a la Catwoman or Howard the Duck; it’s meant to be actively hated by comic fans everywhere. I must be missing something. Perhaps the reason I can’t bring myself to be vitriolic is because I’m not very familiar with the source material. Since I assume most movie-goers aren’t necessarily either, hopefully a brief history of the heroes called “Marvel’s first family” will do everybody some good.

For a VERY brief background: The history of comic books in America is divided into “ages” to help separate different trends in comic storytelling. The Golden Age of comics (1938-1956) introduced American audiences to the modern superhero archetype, and was the genesis of many iconic heroes like Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Captain Marvel, and Captain America. By the end of WWII, however, stories about superheros had declined in popularity, and most of these classic heroes had become little more than glorified firefighters (i.e., boring material for what should be an engaging story). This was exacerbated by legislature in 1954 called the Comics Code Authority, which regulated comic content after convincing the larger public that reading comics was a precursor to juvenile delinquency. (They were wrong, of course; it’s only since the 1980s that we learned heavy metal and then video games were the true culprits, and since banning them we have attained world peace.)

Despite this regulation, the oversight of the Comics Code Authority is held somewhat responsible for the transition to the Silver Age of comics (1956-1970), where superheroes and comics in general became mainstream content in American culture. The stories were not full of the “questionable content” that transformed upstanding youths into James Dean-esque rebels found in mystery and horror comics of the early 1950s, but were not so bland and toothless as the superheroes from that time either. More complex characters got more readers interested, and comics really hit their stride as a medium.

Into this atmosphere, the Fantastic Four were born.

Fantastic Four #1 was released in November 1961, co-created by comic legends Jack Kirby and Stan Lee. Even on its release, these characters were unique and interesting for several reasons. Firstly, the fact that there were four characters in a recurring comic already differed from most comics up to that point which featured at most a Dynamic Duo or temporary team-up of multiple heroes. It wasn’t the first to use this approach; so the story goes, Lee was approached by his boss one day who had learned of the newly-created “Justice League of America” of DC Comics and asked “If the Justice League is selling… why don’t we put out a comic book that features a team of superheroes?”

But while the Justice League might present themselves as a sort of superhero institution, the FF were more of a dysfunctional family that also happened to be a team of heroes. They had arguments about real things, like jealousy and trust, as well comic book things, like as how to stop the planet-eating Galactus from consuming the Earth this week. Sometimes their arguments could even hinder their ability to work as a team. It was a dynamic comic readers weren’t used to, and it proved to be a popular one.

The comic also featured heroes who didn’t have secret identities, eschewing anonymity for fame. This caused the public (in the comics) to be simultaneously awed by and suspicious of the team. Also, like many heroes of the era, the Four were gifted their powers by a chance encounter with cosmic radiation, not from birth like Superman or Wonder Woman. While maybe not directly relatable, this kind of story was a little more grounded in reality than some of the Golden Age stories.

The members of the Fantastic Four team have since gone on to become some of the most enduring and popular characters in comic book history, spanning decades of adventures. For those unfamiliar with its members, they are:

- Reed Richards, aka Mr. Fantastic, who in addition to being one of the smartest men in the Marvel universe also has the ability to stretch his body and limbs;

- Sue Storm Richards, aka the Invisible Woman, who can bend light around her body to make herself invisible and later can generate force fields (because having a team with one woman whose only power is literally “be invisible” isn’t great);

- Johnny Storm, aka the Human Torch, Sue’s brother who can summon flames he can control with his catchphrase “Flame on!”;

- and Ben Grimm, aka the Thing, who has incredible strength physical resilience but whose body was turned orange and stony, and who has his own catchphrase: “It’s clobberin’ time!”

Reed and Sue would later get married, giving the team an even stronger “family” feeling that readers have always found endearing.

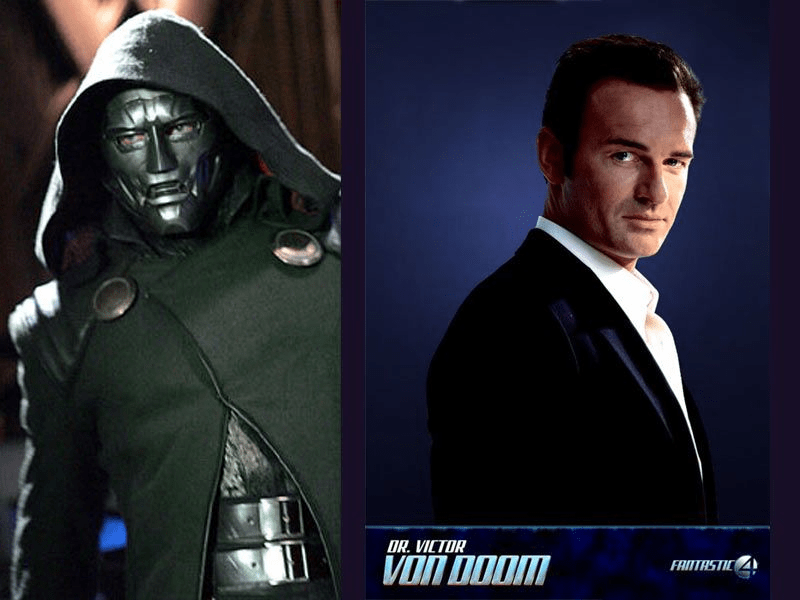

Of course, one can’t mention the Fantastic Four without also acknowledging their nemesis, Viktor von Doom, aka Dr. Doom. Dr. Doom is a terrifying figure in the Marvel universe, feared alongside the likes of Magneto or Thanos in terms of ferocity and sheer evil-ness. He is a genius scientist, like Mr. Fantastic. He learned magic from Tibetan monks and mastered it, like Dr. Strange. He’s the dictator of the small fictional country in Eastern Europe called Latveria. He wears a metal suit of armor and an ostentatious green cloak and hood at all times, striking an imposing figure. His ride “Dr. Doom’s Fear Fall” at Universal Studios still sucks the terror from the very marrow of my being every time I ride it.

But at the same time, he is as much human as any member of the Four, and audiences has similarly latched onto his character as a fitting villain for their favorite team. He also, according to this article from The Atlantic columnist David Sims, is a great example of the marriage between the sometimes deep themes of superhero comics and the inherent silliness of them:

In his first comic-book appearance (Fantastic Four #5 in 1962), he captures the heroes and forces them to travel back in time to steal the pirate Blackbeard’s treasure chest, hoping to claim the wizard Merlin’s lost jewels to power his nefarious magic. He is, even for the era, a delightfully ludicrous creation.

That kitschy tone is part of what makes comic books so special. The medium offers vast dramatic territory for writers and artists to navigate, from the dizzyingly absurd to the most recognizably human. As my colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates has put it, Doom comes from a genre once dismissed as trash, but at the same time seized on by younger generations who understood the story of a tortured outsider.

So now that I (and you) are aware of how much the Fantastic Four team means to comic fans, I think I might understand why so many comic-loving fans might continue to look at the Fantastic Four movies so unfavorably. David Sims sums it up well:

On the page, it’s easy to relate to Doom as a man while simultaneously enjoying his latest ridiculous battle against a godlike alien or dark demon. On the screen, it’s a far tougher balance to strike, which is why Fantastic Four—simultaneously grounded and preposterous—has proven one of the toughest comic-book properties of all to translate.

To someone like me, who isn’t invested in these characters outside the film itself, the goofiness of the scenarios the heroes find themselves in is an acceptable part of their story; in fact, I sort of expect it. Remember, this is a story whose premise involves humans getting superpowers from space radiation. It seems natural that they might use those powers to do something silly. Mr. Fantastic uses his stretchable arms to do an extra-long wave to impress some women at a club.

The Human Torch accidentally activates his flames while he’s skiing, burns all his clothes off, crashes into a snowbank, and creates an impromptu hot tub to look sexy in.

And OF COURSE the Invisible Woman has to take off all her clothes to sneak around, because her clothes weren’t doused in cosmic radiation and how else are we supposed to sell this movie to teenage boys? Executives have families to feed!

It seems completely natural to me that some sort of ridiculousness would follow getting superhuman powers. More than that, I welcome even attempts at fun humor over the “body horror” direction this story could have gone. Imagine yourself getting terrifying powers and not knowing how to use them, estranged from your family and friends for their own good because you don’t know if you’ll accidently hurt them, trying to come to grips with this new body from which you can’t escape. The premise of the Fantastic Four’s story could easily be that of a horror movie on par with The Fly or The Wolf Man.

The closest we get to that kind of story in these films deals with Ben Grimm, aka the Thing. Grimm seems to get the short end of the superpower stick. Unlike his teammates who can essentially turn their powers “off” and pass for normal humans, Ben is now covered with stony yellow skin all the time and is sometimes uncontrollably powerful. He’s too heavy to take the elevator to Reed’s lab atop the New York skyline, and he constantly breaks glasses and cups trying to manipulate them as he did before the incident. In a truly heartbreaking scene, his fiance sees his new form and can’t handle his change, taking off her engagement ring and walking away. In some ways, becoming a member of the team ruins Ben’s life. It’s only with the camaraderie of the other team members and their common goal to protect their city from Doom that Ben at least somewhat comes to terms with his new existence, and even begins to like himself again. He even finds love in the arms of a blind woman, and even though the whole “blind woman loves monster because love is blind” trope seems a little trite, I’d argue overused tropes have staying power and get overused for a reason.

It’s worth noting that Dr. Doom is also rather toned down in the film version of his character, developing metal skin and magnetic powers instead of mastering Tibetan magic.

But even elements of Doom’s story that are horrifying to think about are glossed over by disappointed fans. Doom’s change doesn’t just grant him powers, it drives him mad. At one point, Victor is standing in front of his mirror scratching a cut on his face, and his skin starts to come off like paint, revealing the metallic skin slowly replacing his body underneath. That’s like something from a John Carpenter movie.

Doom’s story is a sort of inverse to Ben’s body horror story. Where Ben finds strength to overcome his helplessness through his relationships, Doom isolates himself and gives in to his darker urges. Of course, this is all set toward taking over the world in a melodramatic, comic book villainous way reminiscent of his comic counterpart. He’s still going to force the team to do what he says by threatening to kill Mr. Fantastic by freezing him with liquid nitrogen and then breaking him. He’s still plenty evil. Maybe it’s because I don’t read the comics and this is more of a “Baby’s First Dr. Doom” that I like because I’m stupid, but I think this Dr. Doom has a really neat dichotomy to him and more than people give him credit for. But it’s understandably disappointing to a fan expecting something more than a less-cool magnetic Darth Vader cosplayer.

These movies DO try to pack a lot into their run times. Think about how much work goes into the origin story of Spiderman or Batman; now add three more Spidermen to deal with. As successful as the Avengers movies are at balancing multiple characters, each major Avenger had their own movie to be introduced and developed beforehand. This is where one big criticism of these films come into play: that “there’s not enough action.” To be fair, there’s NOT a lot of action scenes with traditional superhero square-offs. The teams battle Dr. Doom at the end of the first film in what I think if a decent sequence but is apparently “so stupid!!!” to some. As I’ve mentioned before, however, this film and this team is really more about the members learning to work as a team despite their differences, and the final confrontation with Doom is more a culmination of this character growth than a “Batman v Superman” or “Man of Steel”-style beatdown.

The second film also is short on action sequences, but does two interesting things with its story that I think make up for it. The first deals with the titular Silver Surfer. For most of the movie, the teams is in a race against time to stop the Earth from being destroyed by Galactus, a cosmic being who consumes planets to live. The Surfer is Galactus’ herald, seeking out planets for his master to devour.

But instead of beating the Surfer into submission or even challenging Galactus himself, the team decides to try and convince the Surfer that what he is doing is wrong. They appeal to the humanity of the Surfer (ironically an alien) to save all Earth’s inhabitants. When they DO have to fight someone, it’s their nemesis Dr. Doom, who has now stolend the Surfer’s surfboard and gained the Surfer’s tremendous powers.

The manner in which they defeat him leads into the second thing I like from this movie – the power-switching. At one point, the Surfer’s immense power destabilizes the team’s molecular structure, causing them to temporarily switch powers with humorous results. This in and of itself is nothing new in team-driven stories, especially in comics. However, at the climax of the film, the only way the all-powerful Doom is able to be defeated is by the rest of the team channeling their powers to the Human Torch. Not only does it make for a nice payoff for the “power-switching” storyline, it also deepens the bond between the team members, who trust each other enough to give up their powers for the greater good of the planet. It echoes the themes of the first movies that teamwork is superior to being alone in overcoming obstacles. Again, maybe not anything special for a comic story, but definitely an interesting development for comic movies at that point (the medium the most people would experience the story through).

But I think this is where these movies succeed the most, despite the legions of naysayers online. These aren’t movies with the best graphics or CGI, nor do they have the best fight scenes in superhero cinema (they don’t have a lot of fighting at all, actually). What they do is make you believe that the members of this superhero team are real people in their world, and that they care about each other as a mismatched family. As a purist, I certainly understand being baffled at the directorial choices of changing planet-devouring Galactus into an amorphous space cloud, or turning Dr. Doom from one of the most dangerous villains in Marvel into an off-brand Magneto. But I think most the vitriol for these movies comes more from a disappointment that they didn’t remain a carbon copy of the comics they were based on. If conveying a sense of family and enjoying a silly comic story has always been the goal of the Fantastic Four comics, I don’t think the movies fall as far as so many vehemently say.

In short, I’m not super invested in these films, so the fact that they aren’t a 1:1 telling of their comic material doesn’t keep from enjoying a somewhat dumb yet entertaining story. Yet after learning about where the characters came from, the way I see the movies acknowledge the themes of friendship and teamwork help me to forgive some of their flaws. They were fun for Julia and I to watch, and if you get a chance, I hope they will be for you, too.

Next time we’ll be tackling Daredevil and its spinoff Electra.