I have always been interested in mythology. My parents would read me mythological stories when I was little, and many of the books I chose to read myself were either collections of mythological stories or influenced by world myths. When I was older, I discovered Joseph Campbell and other scholars, and actively studied stories from the Bible to the Mahabharata. My undergraduate degree is in Religious Studies, and while earning my graduate degree in Theological Studies I took every mythology class that was offered. My home library is full of reference books and collections of stories from around the world. My favorite movie, Stargate, is all about the idea that the gods of our past were more than just stories.

In short, mythology has always had a major influence on me. This in itself isn’t that surprising, given mythology’s influence on so much of contemporary storytelling in pop culture today; from superheroes to Star Wars, our modern myths both echo and build upon the stories of our past. But I wanted to do more than just memorize the divine family trees and who killed which monster. I wanted to learn what makes those stories important in the first place traces back to my earliest introductions to the stories themselves. And one of my earliest access points to the ideas of myths as more than just fun stories was MythQuest.

The Show

MythQuest was an educational TV show that aired weekly from August to November of 2001. Its first and only season consisted of 13 episodes. The series follows siblings Alex and Cleo Bellows who are searching for their missing father, Matt. Matt Bellows is an academic who studies myths and the objects associated with them from cultures from around the world. To keep track of these, he builds a computer program called the Cyber Museum that catalogues all his objects. One day, he finds a strange artifact inside a statue that he recognizes as something called the Gorgos Stone.

When he scans it into the Museum, several things happen. The Stone vanishes into the computer, and the Cyber Museum’s entries become much more lifelike. A figure also appears in the Cyber Museum who Matt recognizes as the trickster god Gorgos himself, and talks about taking revenge on the gods who trapped him in his Stone. Matt then reaches out to touch the picture of the Stone and vanishes.

The rest of the series follows Alex and Cleo as they try to find and rescue their father from the Cyber Museum as well as stopping Gorgos from escaping into the real world.

When MythQuest aired in 2001, I loved it. But I was also 10 years old, and enjoyed a lot of things simply because I didn’t have a huge frame of reference for quality. And because I’ve re-examined other media from my childhood that didn’t live up to my memory of it, I decided to give this series a watch as an adult. Luckily, I can say that I enjoyed my time revisiting Alex and Cleo’s adventures, and that the show holds up as well as any given educational media from the late 90s/ early 2000s. Even though I watched it as it aired on our local PBS affiliate, for this recent viewing I ended up watching the show on YouTube. Someone had clearly taped these shows as they aired, based on the quality of the upload. Normally I would encourage people who are interested to support the official release; however, seeing as MythQuest has never been released on DVD nor appears on any streaming service, I’m just glad there’s a glad to watch it at all.

Alexander and Cleopatra Bellows (played by Chrisopher Jacot and Meredith Henderson, respectively) represent the typical complimentary character types that feature in much of adventure media made for children. Alex is a bit of a jock, shooting hoops or skiing on the slopes with his friend Philthy (yes, that’s actually his name) in his free time. He “doesn’t do well with books” and his grades suffer at school. Cleo, on the other hand, is bookish and focused. This gravitation to scholarship and research, however, is perhaps embraced by necessity rather than by choice. Cleo is wheelchair-bound after losing the use of her legs in a accident. We learn late in the season that she used to be physically active as well, rock climbing and snowboarding. Cleo resents being in her chair, and the show devotes an entire episode to her struggle with her situation (which also happens to be my favorite episode). Although they start the show really leaning into these one-note characteristics, as the season progresses both siblings start to become wiser and more complex through their exposure to the myths.

Each episode has the same basic format. After some introduction into the personal lives of Alex and Cleo, the siblings will log in to the Cyber Museum and find a digital artifact. In the first episode, they learn (accidentally) that touching the artifact on-screen actually transports them into the Cyber Museum itself. This is because the artifacts’ images look “so lifelike.” Anyone who used a computer in the early 2000s can attest to the fact that this was the decade humanity achieved peak graphical prowess.

Whoever touches the artifact finds themselves in the role of the main character of a myth associated with the artifact. Alex is the first to find this out. Once he touches the screen, he becomes the Greek hero Theseus in the Museum while Cleo watches him onscreen.

Everyone in the myth sees him as Theseus, and even looking in a mirror shows a face different than Alex’s. Alex, however, can still hear Cleo from outside. The siblings logically conclude that the only way for Alex to escape the Cyber Museum must be to complete the story, in this case slaying the Minotaur as Theseus did. But the danger here is real, and the siblings aren’t sure what happens if you die in the Cyber Museum. Luckily Alex is a jock, and he’s able to kill the beast. Only afterward does he find the same artifact in the myth that he touched in the real world. Once the artifact is touched in the Museum, Alex is returned to the real world. They then learn a lesson or get a step closer to finding their father.

As the show goes on, Alex goes back in multiple times. Cleo also goes into the Cyber Museum, as she finds that she regains the use of her legs when she embodies someone else. Whenever one sibling is in the Museum, the other sits watching and advising one how to complete the myth or give other advice.

But their adventures into the Cyber Museum aren’t just focused on retelling myths. There are several times during the series where the siblings run into Gorgos, the series’ antagonist. Gorgos usually takes the form of a character from the myth and tries to stop Alex or Cleo from completing it in the way the story intends. We learn that Gorgos is a god himself who was jealous that he had no myths of his own and caused havoc in the other gods’ stories. He was so destructive that all the other gods banded together to imprison him. He now wishes to escape the Cyber Museum by finding the Gorgos Stone that Matt scanned in, and take revenge on the other gods by destroying their myths. While trying to keep Gorgos at bay, Alex and Cleo also constantly look for their father to get him out. We learn that Matt is still alive and being kept prisoner by Gorgos, and can see his children in their adventures even though they cannot see him thanks to Gorgos’ magic.

There are a few secondary characters as well. Matt’s colleague Max Asher helps the Bellows siblings once he discovers what they are doing, lending his mythological expertise to their search for Matt. Alex and Cleo have to hide their adventuring from their mom Lily, who tries to be supportive of her teenage children while her husband is missing without a trace. Alex’s friend Philthy and Cleo’s friend Jennie are support characters as well.

And to the show’s credit, I liked all the characters. Alex and Cleo have a funny and endearing sibling relationship, poking at each other but sticking together when it really matters. There’s a scene where Alex, delivering a speech to a crowd as the Egyptian godking Osiris, ad-libs hilariously: “Friends, Egyptians, countrymen. I have a dream that my children will one day live in an Egypt where they will be judged by the content of their character and not by the funny looking animals they wear on their heads. We are gathered here today to witness…me.” He ends with “One small step for a god, one giant leap for Egyptiankind! I’m the king of the world!” And watching Alex and Philthy try to flirt with girls at a ski resort is sufficiently painful and funny.

The other characters are endearing as well: Lily tries to put on a brave face for her kids while trying to support their family, and Asher genuinely tries to help the siblings find their father. One notable exception to this is Matt’s colleague, Barbara Frazier. Initially, she seems as worried about Matt’s well-being as his family. Then, she does a complete 180 halfway through the season, trying to gain control of the Cyber Museum and steal Matt’s job as head of their department. And just as suddenly as she reveals herself to be so two-faced, she’s written out of the show when Asher starts a rumor that Matt has been seen in Egypt, prompting Barbara off to chase and catch Matt doing something nefarious. It doesn’t really affect the show negatively, as she’s such a minor character. But it’s still weird, and I’m not sure why it had to be that way.

The Power of Myth

One of the things I like most about the show is the variety of myths it draws from. Granted, this is only a 13-episode season, so there’s no way to cover all the various mythologies and religions of the world. But the show admirably tries to be diverse, featuring Greek, Norse, Native American, Japanese, Arthurian, Italian, Egyptian, Welsh, Swahili, and Mayan stories. With more episodes, it seems likely that show would have continued to bring many other belief systems into their story. This can be especially eye-opening to someone only casually familiar with the subject of mythology in general. Most of this show’s audience most likely would only be familiar with a limited selection of contemporary retellings of myths, like Edith Hamilton’s Mythology, or (mostly Greek) mythology-inspired programming, like the Percy Jackson series or Marvel’s Thor. The diverse exposure is refreshing.

I also like how the myths they choose are not all simply “hero slays the monster” myths. They start with the Theseus myth to reel in viewers, certainly, but other stories are very different. “Blodeuwedd” is a courtroom drama about whether or not Cleo (as the titular princess) killed her husband the king. “The Doppelganger” has Alex trying to stop his evil double when it escapes the Cyber Museum into the real world and starts slowly draining his life away. “Minokichi” takes place over many years, where Alex (as Minokichi) tries to figure out his spouse’s deadly secret. Even in its first season, the show tries hard to show the varying types of stories there are.

MythQuest also asks critical questions about myths and stories in general, which also sets it apart from similar educational programs. Some of these include: Are “bad” or “evil” gods always completely evil? Are punishments handed down by the gods unfair, and what does that say about the gods who hand them out? Are ancient myths still relevant today? How real is “real”? To that last question, I think the show sums up their opinion in an exchange between Cleo and Alex. When Cleo chastises Alex for trying to change one of the myths based on his personal feelings for a doomed character and tells him “There’s no such thing as a myth!” Alex replies with “There is in there!” This echoes what many of my professors taught in their classes, that myths are both real and not real. They don’t have to describe a true, physical event to have a profound impact on the way we live our lives and be treated as “real.”

There’s even some critique of the male-centric view of mythology in the show. Cleo goes on several important adventures that arguably progress the search for Matt more than Alex’s sessions. Cleo inhabits the Oracle at Delphi in “The Oracle” and uses her prophetic powers to locate where their father will be next, and Cleo actually finds Matt and works with him in Part 2 of “Isis and Osiris.” One of the best lines in this critique is spoken by Cleo in “Blodeuwedd.” To summarize, a Welsh king was told he would be invincible in battle as long as he never married a mortal woman, so some wizard created a woman out of flowers for him named Blodeuwedd. But Blodeuwedd falls in love with another man and ends up tricking the king into making himself vulnerable to being killed, leading to his death.

After the trial where she is found guilty thanks to testimony from the king’s ghost, the king ruefully tells Blodeuwedd “You were the only woman for me.” To which Blodeuwedd replies “I was the only woman you could have…Even a woman of flowers has to be thought of as a woman.” This is driven even further home in my favorite episode, “The Blessing.” Cleo inhabits a Swahili woman in a story too long to go into here. This particular story is more of what we would consider to be a parable than a myth, imparting important themes of perseverance, courage, and faith. I considered recommending that viewers watch it if they don’t watch any other episode, but “The Blessing” is the episode right before the season finale, and doesn’t have the same impact if you aren’t invested in the siblings’ personal struggles. Nevertheless, the message is clear. Women aren’t simply a prize to won or an obstacle to be conquered, and their stories and struggles are just as valid as anyone else’s, says MythQuest.

In short, the show doesn’t just retell stories. It wraps them in the ongoing struggle of the Bellows and helps show the relevance of myths and stories as Alex and Cleo grow due to their exposure to them.

Educational Entertainment

First and foremost, MythQuest definitely succeeds as a piece of educational entertainment. A large part of this success has to do with the show’s focus on mythology itself. While myths certainly have a surface-level value as entertaining stories full of magic, monsters, and colorful characters, the deeper value of myths comes from their ability to teach those listening to them. So it’s no surprise that an educational TV show whose subject is essentially “entertaining stories that teach lessons” would be a perfect match.

Of course, MythQuest isn’t the only attempt to get kids and teens interested in mythology and the lessons they convey. Educational children’s entertainment features a wide variety of TV shows and films aimed at sparking children’s interest. While shows such as The Magic School Bus, Bill Nye the Science Guy, and Zoboomafoo, which focus on STEM subjects, have generally maintained a large cultural presence, the language arts have had plenty of shows as well. Some, such as Jim Henson’s The Storyteller or Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre, are live-actions reenactments of famous stories; others, like Adventures from the Book of Virtues or The Great Adventures: Stories from the Bible were animated. These and other examples usually focused on retellings of various stories from literature and myth, often followed by summations of the moral or meaning contained within them. They’d also usually featured some sort of framing device, such as an omniscient storyteller speaking directly to the audience or a cast of characters finding solutions for modern-day problems in the featured story.

Perhaps the most famous of the language arts shows is Wishbone, a show in which a dog named Wishbone relates famous stories from history and literature while participating as one of the story’s characters. He would do this in order to address some modern-day issue faced by his owner and their family, and by extension an issue potentially faced by the show’s young viewers.

One aspect that sets MythQuest apart from these other shows, however, lies in its season-long arc. For the majority of educational children’s entertainment, its structure is episodic. A teacher can pop in any episode of The Magic School Bus without having to provide a backstory of the characters or the episode’s order in the show’s timeline. Each adventure is self-contained, and by the end everyone is back where they were before (albeit hopefully a little more educated about the water cycle or bats or whatever).

MythQuest, however, borrows from prime-time dramas and makes its framing device into its own story which builds upon itself for the entire season. Alex and Cleo’s adventures in the Cyber Museum change how they approach future adventures as well as increase their knowledge about how to find their father and stop Gorgos from escaping. The status quo changes from episode to episode, building to a season finale that is a culmination of the story to that point. This is unlike the last episode of a season of Wishbone, for example, which is only really a “season finale” in that it was placed last on that season’s episode list.

On the one hand, I think this decision helps make MythQuest a more engaging show compared to its contemporaries in the educational genre. Viewers have a more vested interest in returning next week to see what happens to Alex and Cleo, and as their characters become more complex their interactions with the myths they reenact similarly become more complex. Compare the first episode in which brave yet simple Alex bravely yet simply slays the Minotaur in a straightforward “Hero’s Journey” myth, to the final two episodes in which Cleo and Alex individually experience inward changes in how they view their world outside the myths. You want to learn what Loki did to the Norse gods to deserve his punishment, of course, but there are more pressing questions. Have the kids found Matt in the Cyber Museum yet? Why is Matt’s research partner at the museum so interested in getting the Cyber Museum for herself? Is Alex and Cleo’s mom seriously dating the detective investigating her missing husband, especially after she said she wasn’t going to one episode ago?

The similarity to the season-long structure of entertainment-based TV also helps to attract and maintain older viewers. Educational programming between teen and preteen audiences faces different challenges when it comes to its presentation of information and keeping its audience hooked. Aside from nostalgia, most teenagers won’t be as willing to keep watching a show like Wishbone aimed at younger audiences. Shows featuring characters closer in age to them and more complicated situations are much more likely to keep a teenager’s attention.

On the other hand, MythQuest’s departure from the genre’s norms results in some drawbacks as well. While an episodic format is less dramatically engaging then a season-long story, it does require more commitment to fully experience the story of the show. If you don’t watch episode 7, then you won’t know where the starting point of episode 8 begins. If you want to teach students about the myth of Orpheus, showing episode 4 of MythQuest would not necessarily be the best way to do this. It would require catching the audience up with a “Previously On”- style introduction. There’s also the fact that this first season features several episodes that focus on the struggles of Alex and Cleo to adhere to the structure of the myth in their actions. In the universe of MythQuest, Alex and Cleo must reenact the myth exactly as it is recorded in the real world. If they don’t, their deviation has immediate and often adverse real-world ramifications. So while this is engaging and unique in a genre that is largely focused on simply retelling myths, it may not be best from a simple educational standpoint.

Changing the Myths

One of my favorite aspects of this show is how Alex and Cleo sometimes struggle with maintaining their roles in the myths they are reenacting. Often the sibling actually in the Cyber Museum will be told the ending of their character’s story beforehand by the other sibling watching from the real world. While it may be useful to know what to expect, Alex and Cleo don’t always find content in this foresight. Instead, it more often makes them reluctant to finish the myth the way it was written because of some unfavorable outcome. In the Japanese myth on Minokichi, for example, Alex “lives” many years in the life of the titular Minokichi, finding contentment in first a wife then in two children. Once he learns that the myth’s ending will cause Alex/Minokichi to lose this happiness, he tries everything to make it so he can stay and nothing will change. “I’m happy here,” he tells Cleo. It’s only reluctantly that he finishes the myth and returns, somberly, to the real world.

This struggle comes to a head during the episode on “Sir Caradoc at the Round Table.” Alex becomes the titular Sir Caradoc at King Aurthur’s court of Camelot. He of course knows the story of Camelot and its tragic fall thanks to Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere’s affair. He decides that he is going to try to stop their relationship from betraying Arthur and the kingdom, and actually finds an unlikely ally in Merlin who recognizes him as Alex Bellows. At first, he’s shocked that a character in a myth would know his true identity. Cleo reminds him that Merlin is a figure who lived backward through time, however, and would therefore be more likely to know things outside his own story. Alex is therefore further convinced that he can save Camelot and does everything he can to keep Guinevere and Lancelot apart.

Instead of ensuring the survival of Camelot, though, Alex instead succeeds on the changing the myth so much that the effects spill over into the real world. A book of Arthurian legends physically changes in Cleo’s hands outside the Cyber Museum, and neither Cleo nor the mythologist Max Asher can remember the myth ever having played out another way. Importantly for Alex, now they don’t know how they myth will end or what dangers Alex must avoid in order to get home. In the end, Lancelot and Guinevere are caught by Arthur anyway, and Sir Caradoc/Alex ends up getting arrested for his part in the conspiracy. It’s at this point that Merlin reveals himself to be Gorgos, preying on Alex’s noble nature in order to irrevocably change the myth for his own ends. Alex eventually sets the myth right by honoring an oath he made that would result in his death, returning honor to Camelot.

In one of my favorite scenes in the whole show, Alex briefly enters a myth from the pre-Egyptian Avia culture, which their scholar friend Asher explains concerns two brothers and their eternal struggle for kingship over each other. When Alex enters the myth, however, the world is empty and white save for a solitary figure on a throne and a few objects. The figure is one of the brothers, and he explains that he finally was able to overcome his brother in battle. Once he did, however, the world started disappearing. Instead of constantly fighting, the myth was changed, and so it and its influence are disappearing forever. When Alex barely makes it back out, he asks Asher to explain the myth to them. Asher, however, suddenly can’t remember what he had mentioned mere moments ago. And as far as my personal research has turned up, there is no pre-Egyptian culture of Avia.

In this way, the show contrasts the way in which myths are viewed and honored. Both Gorgos and the Bellows feel the need to alter the myths, albeit for different reasons. However, in the universe of MythQuest the myths absolutely cannot be altered. If they are, terrible consequences are felt in the real world: a massive earthquake rocks the world when Alex tries to free Loki before Ragnarök, and the book of Arthurian myths physically changes along with memories of the story’s previous telling, as mentioned above. The series tries to rationalize this by arguing that these myths have shaped their respective cultures and by extension the world in which we live. The more well-known the myth, the more foundational it is. If the myths and their lessons are changed, then the world as we know it would cease to exist.

That’s a lesson that’s not always easy to accept, especially the more personally you associate with these stories. In the second episode “Hammer of the Gods,” Alex embodies the Norse god Loki’s son Vali right after Loki has been imprisoned for his misdeeds by the other gods. Even after learning why Loki deserves his punishment, he fights to free the trickster god, going so far as to steal Thor’s hammer to break his father’s chains. But Alex isn’t especially attached to Loki himself, but what Loki represents. He feels that if he lets down his “father” in the myth, then he’ll be letting down his real father Matt by not finding him in the Cyber Museum..

In another myth, Alex portrays Orpheus traveling to the Underworld to rescue his dead bride Eurydice. As in the real-world myth, Hades agrees to let her be led back to the world above, under the condition that Orpheus cannot look back at her until they are out in the sun. As Alex and Eurydice ascend, Alex begins to feel more and more sympathetic for her and for Orpheus, and even after he learns that the myth ends with Orpheus looking back and losing his bride, he almost can’t do it. Once he leaves the Cyber Museum, he and Cleo both agree that the punishments of the gods aren’t always fair to those hearing these stories.

Many times in the show, both Alex and Cleo begrudgingly accept the endings of the myths, despite the gods and their judgements on mortals often being “not fair” to the siblings. Gorgos seems to be slightly sympathetic as well, from what little we know about him. All we know is that he was jealous that he had no myths about him and the gods punished him to be eternally trapped in a stone for it. But the difference in motivations end up being the key. Gorgos is a villain who is changing stories for malicious reasons, and so of course he must be stopped. Alex and Cleo try to make changes from a good place but they don’t understand the importance of maintaining the status quo; once they learn about this importance, they stop trying to change the myths. Life isn’t always fair, unfortunately, and the purpose of myth (especially poignant myths with staying power) is to teach and prepare their listeners for life.

And the myths DO change them. Cleo’s experience in “The Blessing” gives her a fresh outlook on being in a wheelchair, teaching her that her disabilities can’t stop her from living a full life as long as she appreciates what she has. Alex, who hates school, is inspired in the finale “Quetzalcoatl” by the great Mayan teacher of the same name in a way no real-world teacher he’s had ever has. Some of the last lines of the series are of him saying they need to dive into research to prepare for the road ahead instead of jumping in blindly like he does in the series’ beginning. And as a tool to educate young people about the role of mythology and stories in the 21st century, I think showing this change is how MythQuest succeeds.

Final Thoughts

As I mentioned at the beginning, “MythQuest” only has one season of 13 episodes. The last of these episodes introduced plot elements that promised more adventures to come with greater stakes. Cleo, Alex, and their allies have learned how to navigate the Cyber Museum and nailed down what their purpose is: to find the Gorgos Stone before Gorgos does and seal him away again, and to rescue their dad. A mysterious stranger even appears in the last episode to help them, revealing that he possesses a piece of the Gorgos Stone in the real world that was entrusted to him by an ancient order of guardians in the event Gorgos ever escaped. It seems like there’s actually a chance they’ll succeed. Philthy is there.

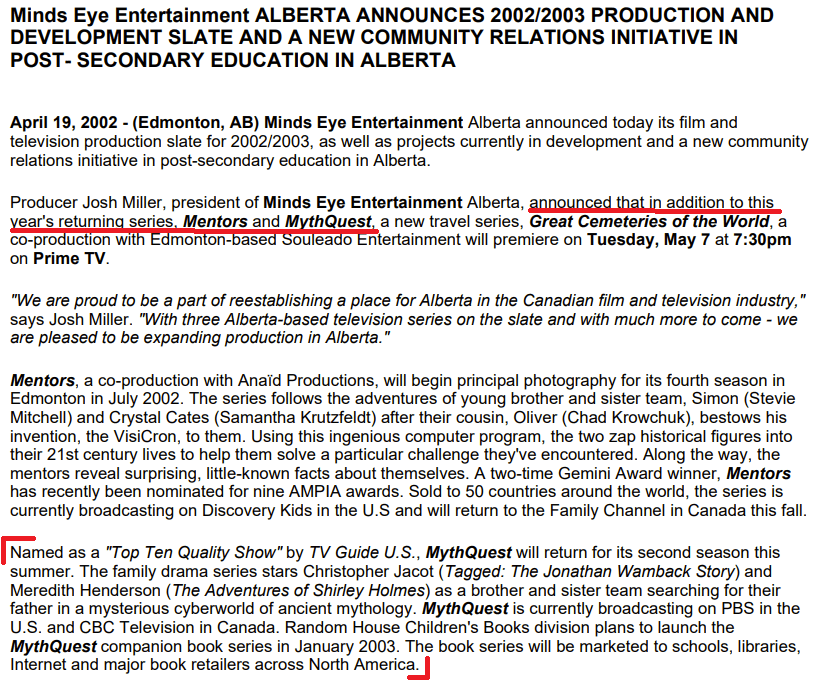

The show’s future looked bright as well, and I’ve even found articles as well as statements from Mind’s Eye Productions which both talk about the future plans for the show.

But despite these articles and the show’s cliffhanger ending, the series wasn’t renewed. For 20 years, the only new media released are a few novelizations of 4 of the 13 episodes. Matt is still trapped in the Cyber Museum, and Alex and Cleo are still looking for a way to free him. Gorgos is still searching for his Stone and plotting his revenge on the gods and our world.

Anyone who knows me well will attest that, when it comes to media, there are a few things I can’t stand: spoilers, recasting an actor or actress for a sequel (looking at you, The Mummy 3), and good stories that don’t have an ending. MythQuest has been and continues to fall into the last category for me. I feel like we all have some sort of unfinished media we wish would come to a satisfying conclusion. For my wife, it’s the TV show Kyle XY. For me, it’s Clive Barker’s Abarat book series. For the world at large, it’s George R R Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire.

So naturally it frustrates me that this story I got invested in as a 10-year-old will most likely never be officially finished. I actually reached out to the production company, Mind’s Eye Pictures, to see if there were any plans to somehow wrap up the story. Unfortunately, I didn’t get a response, but I’m not too optimistic. After all, the original actors are all older, and if the story wasn’t popular enough 20 years ago to warrant continuing, I doubt it would be picked up again even for an ending book or comic now.

So: does MythQuest live up to my childhood expectations? Yes. Despite being a little corny, I’m glad I was able to watch it again after so many years. If someone you know is interested in mythology and they’re a fan of shows like Bill Nye and The Magic School Bus, I would bring it up on YouTube and give it a try.

To end, I’d like to share a short personal story. As I said at the beginning, I was very into this show when it aired in the latter half of 2001. My dad would tape it from the local PBS affiliate for me and we would watch it together. When we popped in the tape for the season finale, however, we realized that the local station had aired a basketball game instead of MythQuest. My dad actually called or emailed someone at the station to see when we could see a rerun of the finale, only to be told that it wasn’t going to air again. Well, of course I was very disappointed. Then a week or so later, we received a VHS tape in the mail marked “MythQuest Finale.” Someone had actually taken the time to record the finale episode and send it to me so I could watch it. I’m sure my dad still has the VHS somewhere in his library of specials and movies on tape. It may not have seemed like much for that TV station employee, but it meant the world to me at the time, and I’ve never forgotten it.

So if you’re interested, the entire series is currently on a YouTube playlist here. Watch it, leave a comment, and cross your fingers that the nostalgia machine will deliver us a satisfying end to this forgotten gem.

I remember watching this show as a kid in the early 2000s. Its what got me inspired to read more about myths and different cultures. I had forgotten this show for a long time since I left high school, and recently remembered it.

Thank you for writing an article about MythQuest. It’s great to see it talked about it even now. And thank you for the youtube link. I’ve missed this show a lot and I’m glad I get to watch it again.

LikeLike