Why It Was Written

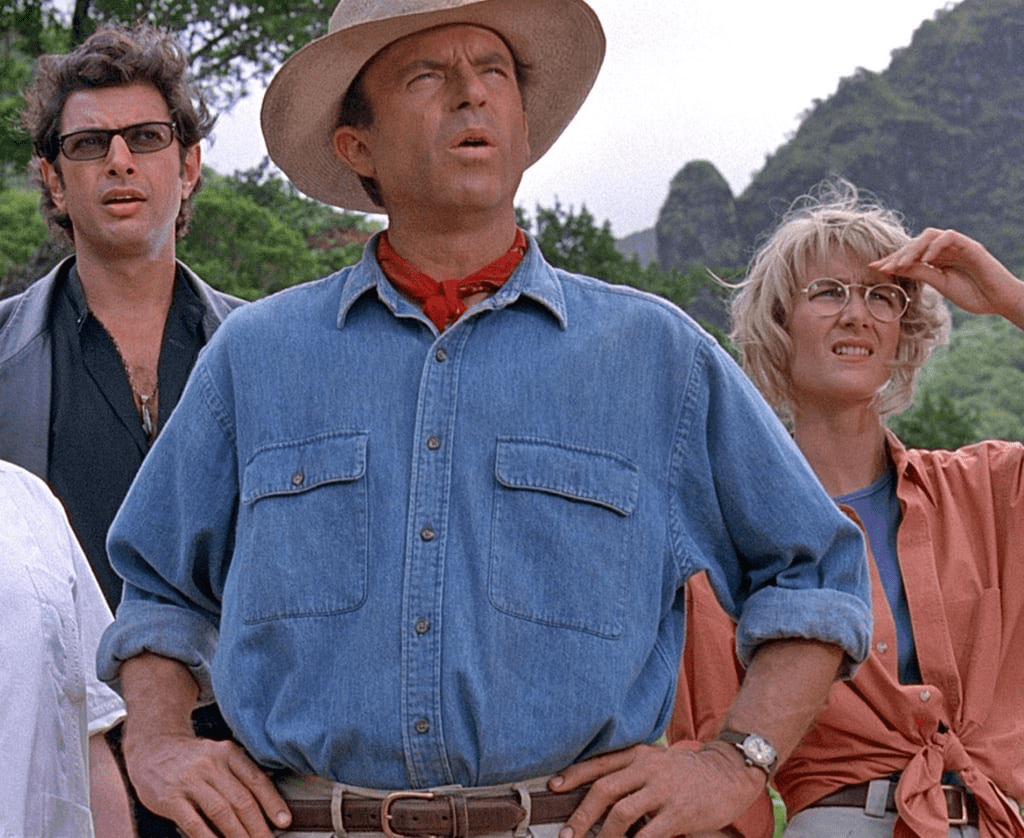

Michael Crichton’s novel Jurassic Park was a huge hit when it released in 1990, and the 1993 movie adaptation by director Steven Spielberg further cemented the story as a staple of science fiction. The cautionary tale about scientists and capitalists playing God by resurrecting dinosaurs, only to have their creations escape their control with disastrous results, has been well-loved since its release. Both the film and the movie were so well-loved, in fact, that fans of both eagerly encouraged Crichton to write a sequel. Crichton, who had never written a sequel up to that point, was hesitant to do so. According to him:

” [A sequel is] a very difficult structural problem because it has to be the same but different; if it’s really the same, then it’s the same—and if it’s really different, then it’s not a sequel. So it’s in some funny intermediate territory.”

In the end, however, Crichton agreed to write his first and only sequel. He named the 1995 book The Lost World after Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 book of the same name. Two years later, Spielberg would make his own adaptation of Crichton’s sequel, also titled The Lost World. Both film and book were successful, ensuring that we would continue to to watch businessmen and scientists open dinosaur theme parks and become victims of their hubris for decades to come.

Summary

Four years after the disaster at Jurassic Park and the closure of InGen, the company which made the dinosaurs, survivor Ian Malcolm is approached by a wealthy scientist named Richard Levine. Levine believes that not all of InGen’s dinosaurs were destroyed when the Costa Rican government carpet bombed Jurassic Park, and that other InGen dinosaurs still exist on a remote Central American island. He eventually discovers the location of the island, called Site B by InGen, and travels there alone without Malcolm or his research team. When Malcolm receives a troubling satellite phone message from Levine, he sets off with their team to rescue his colleague. Malcolm travels to Site B, located on the small Isla Sorna, with engineer Jack Thorne and his assistant Edie Carr, as well as two children R. B. “Arby” Benton and Kelly Curtis, who have been helping Levine with his research and who stow away on Malcolm’s boat. Unknown to Malcolm, a rival genetics company sends their own small team to recover InGen’s research and materials headed by the ruthless Lewis Dodgson. Another of Levine and Malcom’s acquaintances, Dr. Sarah Harding, travels separately to the island.

Upon landing on the island and locating Levine, they discover that Site B was where InGen grew and hatched the dinosaur before shipping them to Jurassic Park. The island was abandoned when InGen shuttered, and the dinosaurs have been free to create their own isolated ecosystem in the years since. Levine wants to stay and observe this lost world, while Malcolm and Thorne reluctantly help him set up observation equipment before their extraction helicopter arrives. Dodgson and his team, meanwhile, begin traveling around the island stealing eggs from dinosaur nests for transport back to their company. While attempting to rob a T-rex nest, however, their equipment fails and they become lost in the jungle. Malcolm and Levine’s team also run into trouble when Eddie brings an injured T-rex baby back to their trailer to treat, and its parents come looking for their baby. The group have run-ins with various dinosaurs and spend a harrowing night avoiding T-rex, carnotaurs, and velociraptors; Eddie falls victim to the latter. Dodgson entire team is wiped out, and he meets his own end at the jaws of the baby T-rex he injured. Malcolm and the surviving others are finally able to escape on an abandoned boat, leaving the lost world to its fate.

My Thoughts

One of the first things I noticed about reading for this entry was how much better this book was compared to the other books in this series. This is of course because Michael Crichton is an internationally-acclaimed author, and for the most part the other books haven’t been the same level of quality as The Lost World. So that makes it a little more difficult to point out flaws like the rest of the entries.

Firstly, there’s the interesting place this book occupies in relation to both the original book and film. On the one hand, a sequel written by the author of the original book as a continuation of the original story with returning characters would naturally be considered a sequel to the first book. The hubris of InGen and their scientists messing with the Diiiiino DNA is on full display again. But the movie adaptation of Jurassic Park made some notable changes from the original. The movie version’s head of InGen, John Hammond, is a kindly and well-meaning man who ultimately has more money and ambition than sense, and as he escapes his island he realizes that it was foolish to try to control nature in the first place. The book’s version of Hammond, however, is ruthless capitalist who plans to open the park despite the deaths that have taken place there, and in the end he gets what’s coming to him, dino-style. In The Lost World, Hammond is absent and presumably has met with his fate from the first book, so The Lost World is a sequel to the original book.

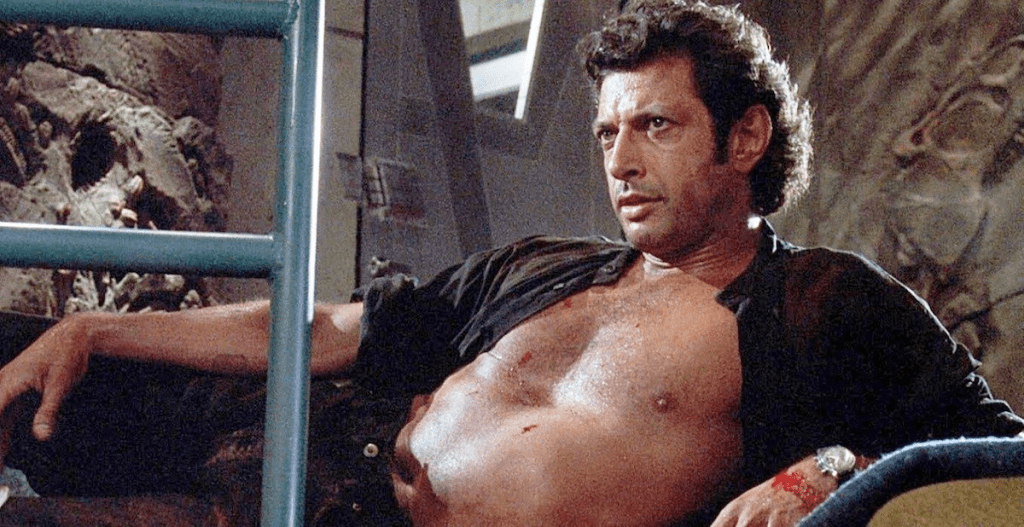

On the other hand, the scientist Ian Malcolm was one of the island’s casualties in the book, yet was a survivor in the film adaptation. His portrayal by Jeff Goldblum helped to make the character an audience favorite. So Malcolm miraculously survives to be the protagonist of the sequel. In this way, The Lost World is clearly a sequel to the original film.

Other conflicting details place Crichton’s book nebulously as a continuation of both the original novel and film, despite those two stories having some importance differences from each other. But this is the reason I started this series in the first place, so it’s not something that ruins the experience for me.

Throughout this series, the strongest characters of the respective books have been those who have already been fleshed out in their original films; E.T. and Luke Skywalker were the best-written characters in their respective books because they had already complete characters in their films. The actual creations of many of these authors were not as impactful, despite their roles as new antagonists for our heroes. It was a welcome surprise, then, that alongside returning character Ian Malcolm the book’s other characters felt as fleshed-out as he did. I especially felt a continued frustration and annoyance with Malcolm’s scientist friend, Richard Levine. Levine is a scientist who is obsessed with his research to the point of ignoring clear danger to himself or others. He is the one who travels to the dangerous dinosaur-infested island with no gear, no team, and no plan other than to get there before anyone else does, and when Malcolm’s team risks their own safety to rescue him, he insists on staying to set up monitoring equipment before he will leave. He also constantly condescends to the people around him (with the exception of Malcolm), making it even more infuriating that his colleagues are risking their lives to help him.

And in the end, despite his fervent assertions on the importance of remaining as apart from the subject of his study as possible, he is constantly meddling with the island’s environment. His most egregious act comes when, safe in a camouflaged observation tower, he unwraps a power bar and then carelessly lets the wrapper float down to the ground. Not only does this go against his own insistence to not interfere with this “pristine” lost world, the wrapper later attracts the attention of a pack of velociraptors who would otherwise have passed the tower by and ends up getting one of the team members killed by them.

But the best thing about Levine is that he is not the villain of the piece. Normally, Levine would be perfectly fit to receive some dinosaur-themed comeuppance for his disregard for other humans in his quest for “objective scientific truth.” The actual villains are certainly punished for their villainy, and similar characters in other Crichton books have their evil actions punished appropriately. But Levine lives to escape the island at the book’s end. He ultimately fails in his objective, as I’ll discuss in a moment, but he is allowed to live. It’s a subversion of expectations which I appreciated from Crichton.

One thing Michael Crichton’s books are known for besides excellent action is the amount of science that he puts in to his books. The horror of the original Jurassic Park is not simply that dinosaurs are hunting people on an island, but that people defied the will of nature and are being punished for their hubris. Crichton constantly references scientific theories, statistical models, and real-life case studies to underscore the opinions of his protagonists. Whether these explanations are more science or more fiction, it gives the universe of his books that much more plausibility.

In The Lost World, this culminates with the explanation concerning the fate of the dinosaurs on the island. In the original book, the dinosaurs were genetically grown to need a steady supply of lysine they couldn’t find easily in their environment in order to make them dependent on humans for their survival. As Malcolm famously noted, however, “Life, uh, finds a way,” and the dinosaurs in the wild eat plenty of lysine-rich plants (or lysine-rich plant-eaters) to overcome this manmade obstacle. Here, however, it is revealed that the dinosaurs at Site B were doomed from the start because of a simple overlooked detail of their creation. The scientists raised the dinosaurs by feeding them not chicken or beef but sheep meat, who (according to the book) are notorious vectors for prions, tiny but deadly viruses of the brain that cause death.

Because the dinosaurs were fed this tainted meat, the researchers were unable to stop the proliferation of a sickness they could not account for. Upon being released into the wild, the dinosaur populations seemed to stabilize themselves and create a unique ecosystem; ultimately, however, they are doomed to be destroyed within a few generations. So despite the best efforts of the InGen scientists or Richard Levine to let life find its way, humans kept that from being possible. It’s an ending that’s a little less hopeful or reverent than that of the films, but fits in perfectly with Crichton’s science-based MO.

Unfortunately, you can’t really talk about the science of Michael Crichton without acknowledging some of his less-enlightened ideas. Science fiction, like the fictional genetics of Jurassic Park or the advanced robotics of Westworld, falls outside the reach of contemporary science while containing just enough plausibility to seem possible. But pseudoscience or so-called alternative science is at best more fiction than fact and at worst detrimental to the integrity of science. Crichton’s best (or worst) example of this is his 2004 book State of Fear, in which eco-terrorists use technology to create man-made “natural” disasters (such as tsunamis) in order to convince the public about the dangers of global warming. The fact that these “natural” disasters, which can kill and displace hundreds of innocent people, are in fact fabricated by fanatics says a lot about Chrichton’s views on the idea of global warming. In fact, one of the heroes of the book spends one chapter detailing how the massive shifts in Earth’s weather are in fact due to a great global cooling. He criticizes the idea as one of many theories in the same misguided way that evangelicals deride evolution for being “just a theory” (i.e., with great ignorance). And despite the numerous graphs, citations, and 20 pages of bibliography, Chrichton’s work has been infamously credited with popularizing the “Antarctic cooling controversy,” which is exactly what it sounds like.

So despite the entertaining way Chrichton is able to interweave fantastic happenings like android uprisings or dinosaur rampages with their in-universe scientific “proofs” that draw on real-world research, there’s no way to read Chrichton as a master of science fiction without allowing for a grain of salt. The science of this book and the original largely deals with genetics and animal behavior, so this controversial side of Chrichton isn’t really present. It certainly doesn’t get in the way of the action or exciting setting of the story. But considering the leaps that both genetics and animal behavior have had in the 30ish years since the book was written (did you know that alpha males don’t exist?), who knows what Chrichton may have gotten wrong. Then again, maybe 97% of the scientific community is wrong and Chrichton’s ghost will have the last laugh.

I can say confidently, however, that despite any potential scientific misinformation, the book is definitely better than the film of the same name. While both the first book and first movie are staples of the science fiction genre in their own rights, The Lost World book is superior to The Lost World movie in nearly every way. For one thing, the plot makes more sense. The book is a rescue mission thwarted by Levine’s single-mindedness, the failure of the original InGen scientists, and incompetent employees from a competitor. The movie, meanwhile, is only a rescue mission for Malcolm, whose girlfriend Sarah chose to go the island of her own free will. The dinosaurs and their ecosystem are alive and thriving, completely undercutting the theme about InGen’s hubris in overlooking the dangers of disease-filled meat. And the villains are a literal private corporate army with heavy equipment, vehicles, and guns. A number of men are individually outclassed by dinosaurs, sure, but the operation manages to subdue, capture, and transport a full-grown T-rex and its child to the US. The villains in both books get their deserved comeuppance by way of death by T-rex baby, but that just seems more like the movie copying a good idea from the superior novel.

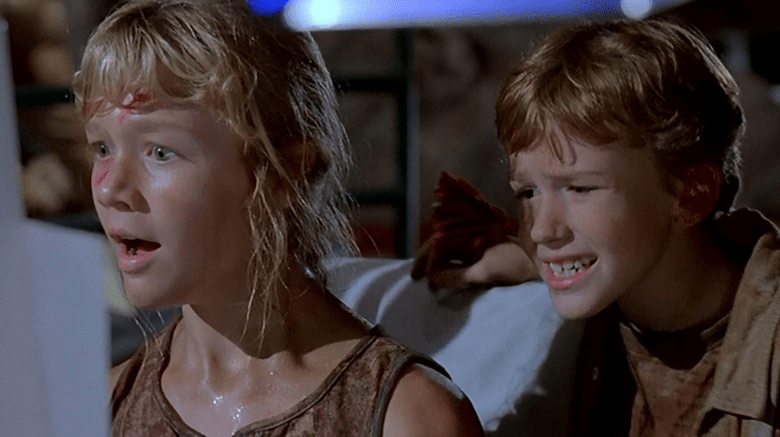

The way in which the novel handles its child characters is better than the film’s decisions as well. The book features Levine’s two young assistants, a boy Arby and a girl Kelly. The movie’s child character, a girl also named Kelly, is Malcolm’s estranged daughter. Now I understand that the theme of the film, according to Spielberg, is “family.” In light of this, it makes sense for the vulnerable child who needs protecting by the heroes is more impactful if she is related to them. We care about Kelly that much more because she’s Malcolm’s daughter, and even more because we see that he wans to connect with her but may have that chance taken away by the island’s dangers. Arby and book Kelly aren’t related to anyone else on the island (Levine recruited two children to do his research to throw off the corporation spying on him, totally natural), so they don’t possess this extra-endearing status.

But while both children are helpful in thwarting the dinosaurs of their respective islands, the ways in which they are helpful is telling. Soon after landing on the island in the book, Arby splices into the extensive camera network of the island, allowing the team to see and prepare for various dangers during their hectic adventure. Book Kelly also aides the team by finding an escape route when they are cornered by velociraptors, leading them to safety. Both children are also intelligent and are able to contribute to the observations about the island and its prehistoric inhabitants in a useful (to us the reader) way.

Conversely, Movie Kelly is too scared to be making any scientific observations, though we can perhaps give her a pass on that point due to her situation. Aside from this, she is helpful precisely one time. During a harrowing scene in which velociraptors chase Malcolm and Sarah, Kelly is able to dispatch one of the raptors with her impressive physical prowess. And by that, I of course mean she uses gymnastics to punt the raptor through a wall.

Yes, it saves her father’s life. But while the actions of the Arby and Book Kelly are at least believable, death by gymnastics is frankly just silly.

There are a few aspects of the film I did like. If the theme of Spielberg’s movie is “family,” he does it well with small intimate moments between Malcolm, Sarah, and Kelly that feel genuine. Also there is one scene in particular in which a group of soldiers are marching through a field of tall grass and are picked off by velociraptors. The raptors move like sharks through the grass of the field and it’s very cool-looking. In fact, I remember that when this film came out (when I was 7 years old and not allowed to see it), this scene was all my friends could talk about.

And of course, nothing can beat a John Williams score.

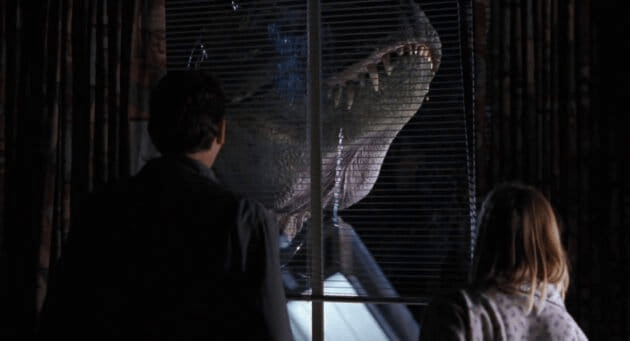

There are other aspects of the book that prove its superiority to the film adaptation. The world of the book feels more “lived-in,” with pages dedicated to describing the movements and interaction of various dinosaurs that an action movie just doesn’t have time for. There are mysteries to the island of the book that are never answered and therefore increase their appeal, such as a short encounter with a predatory carnotaurous which has evolved color-changing skin like an octopus which are never mentioned again, or the pages of InGen internal memos degraded with age and full of mystery. And perhaps most importantly, the book does not end with an extended scene of a T-rex rampaging through downtown San Diego. The destruction isn’t a huge misstep (although I’m sure some of the references onscreen are funnier to someone living on the West Coast), but it’s a rather ham-fisted way of driving home the theme that “dinosaurs don’t belong in the modern world, nature meant for them to go extinct and Man is paying for his hubris” as a T-rex stomps on wrecked cars past an Exxon station. The book was a bit subtler. Plus, the film commits the sin of killing the dog in a movie that isn’t exclusively about how great dogs are.

All in all, it was nice to have a higher-quality entry in this series. I would recommend both books and both movies to get the full Jurassic experience. I’m not sure about going much further than that, however.

We’ll end our series with our final entry just in time for Halloween: the sequel to both Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical of the same name, Frederick Forsyth’s The Phantom of Manhattan.

Pingback: Semi-Sequel Series: “E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial” and “E.T.: The Book of the Green Planet” – Culturally Opinionated