Why It Was Written

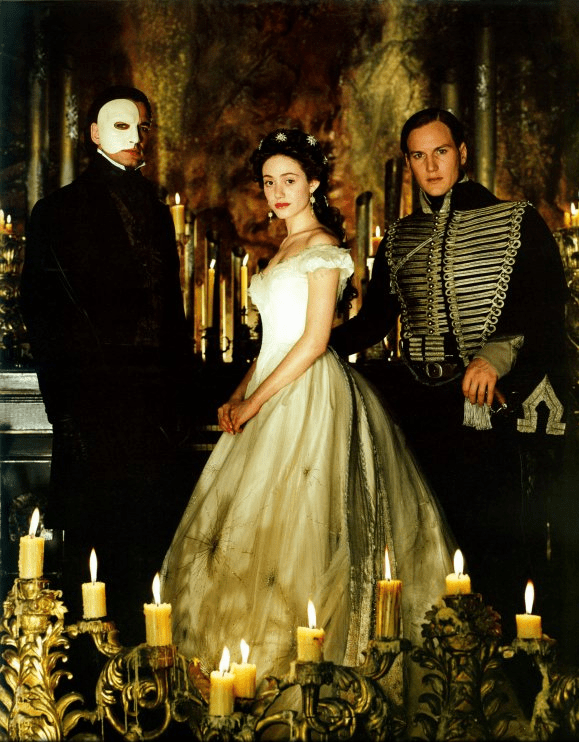

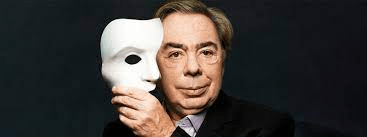

Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Phantom of the Opera opened on West End in 1986 and premiered on Broadway in 1988, and has since become the longest-running Broadway musical of all time. Based on a 1910 novel of the same name by Gaston Leroux, Webber’s version was both innovative in the theater world as well as extremely entertaining for audiences. Even theater fans who say they don’t care for Webber’s work can’t deny the immense popularity and staying power Phantom has had both in the theater as well as in the larger culture beyond.

So it should come as no surprise that Webber began toying with the idea of a sequel soon after. By 1990, Webber and author Frederick Forsyth began collaborating on said sequel, but eventually parted ways due to creative differences. Forsyth took the concepts and basic story he and Webber had created, publishing them as his novel The Phantom of Manhattan. Until the first premier of Webber’s 2010 sequel, Love Never Dies, Forsyth’s book was the only sequel to the story of Christine Daae, Raoul de Chagny, and the Phantom.

Summary

I’ll keep the summary as brief as I can.

The book opens in 1906 with the deathbed confession of Madam Giry, the dance instructor of the Paris opera house until the great fire that destroyed it several years prior. She confesses that, as a young woman, she rescued a deformed boy from a traveling circus and hid him in the subterranean vaults of the opera house. This boy, whom she names as Erik Muhlheim, is a musical and engineering genius, becoming known as the Phantom of the Opera for his mysterious existence within the opera house’s walls. After Erik falls in love with one of his musical pupils, Christine Daae, and kidnaps her into the depths of the vaults, Christine’s lover Raoul de Chagny chases the Phantom into his hidden home to rescue her. Erik is finally moved to let Christine go, and disappears before he can be apprehended by an angry mob. Madam Giry reveals that soon after, she and her daughter Meg smuggled Erik out of France onto a ship bound for America. On her deathbed, she begs for her lawyer to travel to Manhattan to deliver a letter to Erik.

Erik, meanwhile, jumped ship to avoid going through the customs on Ellis Island and washed up on Coney Island. With the help of his genius for machines as well as help from a young man Darius, Erik manages to become rich by building rides for various Coney Island park owners. He moves in to Manhattan proper and makes even more riches by manipulating the stock market. He eventually becomes so rich that he decides to build an opulent opera house after being refused entry to the Metropolitan Opera House by the social elite of Manhattan. He silently backs Oscar Hammerstein I’s plan for the project. During the construction, Erik receives Madam Giry’s letter. His assistant Darius, who is consumed by a lust for gold on behalf of the God of Greed, Mammon, worries what this letter means for his eventual inheritance of Erik’s riches.

Erik uses Hammerstein to convince Christine de Chagny, now a world-renowned opera singer and wife of Raoul, to sing at the inaugural performance of the new opera house. She travels with her son Pierre to America. While there, Christine and Erik are reunited in secret, where Erik confronts Christine about the contents of Madam Giry’s letter. According to Giry, Raoul was injured as a boy trying to stop a mugging and cannot have children. It is also revealed that Christine returned the Phantom the night after the great fire and their confrontation, and that Pierre was the result of their night of passion. He is Erik’s son, which no one knows but Christine, Raoul, and Erik. Christine tells Erik that she will tell Pierre of his true parentage in five years when he becomes a man, and Erik agrees to wait until then. However, after Christine leaves, Erik vows to reclaim his lost son as soon as possible. Darius overhears this development and vows to ensure Erik’s inheritance falls into his own hands rather than Pierre’s.

Erik’s opera, The Angel of Shiloh, turns out to be a Civil War-themed drama about a Southern woman falling in love with a Northern soldier. The soldier is scarred by battle and eventually lets his one-time love marry another with his blessing. During the first performance, Erik secretly plays the role of the malformed soldier and sings with Christine (the Southern woman) to great critical acclaim. At the last performance, Erik convinces Christine to visit him alone the morning before she leaves for France.

The morning comes, and Christine meets Erik in Battery Park. Erik expresses his love for Christine, and she promises again to tell Pierre of his existence. Raoul and Pierre, as well as several other characters, discover the meeting in the park. Suddenly, Darius appears and shoots Christine, only to be immediately killed by Erik in retaliation. As Christine lays dying, she tells Pierre that Erik is his true father. Raoul gives Pierre the choice of returning to France with him or starting a new life with his real father. Pierre chooses Erik, and the two walk off into the predawn mist of Manhattan. The book ends by asserting that Erik and Pierre lived happily together as one of the richest families in America, contributing the arts as well as taking care of wounded and disfigured people.

My Thoughts

In a way, I’m glad that I saved this book for last. Of all the books I’ve read for this series, this is the one that did not need to be written the most of all. The story of The Phantom of the Opera, whether the original by Gaston Leroux or the Webber musical, is complete as one story. There are notable differences between the two versions, to be sure, and those differences can change the themes of the Phantom’s story. Nevertheless, both versions present complete and satisfying conclusions, even with the mystery concerning the Phantom’s ultimate fate leaving the story open-ended. To be fair, I can certainly understand that there’s always a hunger from audiences for more of a story they like, especially when the original is open-ended as to the fate of its characters. The temptation is always there to write Phantom II: Phantom Harder to give the people what they want.

But much more frequently sequels don’t add anything worthwhile to the original, instead encumbering a satisfying ending with disappointing and unnecessary continuation. An open ending, in my opinion, is an invitation for the audience to continue the story for themselves, not for studio executives to milk a franchise for all its worth. In short, The Phantom of Manhattan takes the open ending of the original and takes it in a direction it didn’t need to go.

As just a small note: even though Phantom of Manhattan purports to be a “continuation” of Leroux’s book, the fact that it was commissioned by Webber to act as a framework for a sequel to his musical ties it more closely to the Webber version. Because of this, I’m going to treat the book as a sequel to Webber’s adaptation here.

Let’s start with the biggest question the novel introduces. At the end of Phantom, the Phantom kidnaps Christine, brings her to his subterranean lair, and forces her to make an impossible choice: She must either declare her love for her fiancé, Raoul, which will prompt the Phantom to kill Raoul in anger; or she must declare her love for the Phantom and spend her life with him, at which point Raoul will be spared. In the end, Christine finds a third option. She shows the Phantom the first real kindness he has ever known in his life to appeal to whatever goodness he has in him and kisses him without his mask on. The Phantom is so touched that he lets both Christine and Raoul go, realizing he wants Christine to be happy even if it is not with him. He has an epiphany about his life, and disappears to escape the angry crowd crying for his blood. Christine escapes with Raoul, and they all live happily ever after.

Except that, according to Phantom of Manhattan, after narrowly avoiding a terror-filled life with the Phantom, she decides to go back to him the very next night for a night of passion with her abductor. As ridiculous as it sounds (and is), part of me understands that there needs to be some lingering feelings between Christine and the Phantom for there to be any interesting tension in the book. And there’s no way that Christine’s child could secretly be the Erik’s if they hadn’t had one night together before not seeing each other for 10 years. But to anyone who has seen the musical, Christine’s choice is so bizarre. She spent all that time trying to get away from the influence of the Phantom, and when she’s finally free after helping him to discover his good side, she seemingly rewards her kidnapper with a late-night booty call? Even for a story about old flames being rekindled and how “Love Never Dies,” this entire premise is baffling.

And speaking of baffling plot points, we learn about halfway through the book that Raoul has known for their entire marriage that Christine’s child is not his. He knows because he is physically incapable of having children. When he was a young man, Raoul tried to save a woman from being assaulted and was shot in the groin for his trouble. So when Christine presumably told him that she was pregnant a few months after their marriage, there’s no way he wouldn’t have known whose child it was. Now that is the conversation I as a reader would like to see: Christine casually mentioning that Raoul’s going to be a daddy a week into their honeymoon.

And am I the only one who thinks that what happens to Raoul is totally unfair? When we last saw Raoul in the musical, he was risking his life to rescue Christine from the hands of a madman and give her a life of luxury as the Vicomtesse de Chagny. He learns that his new wife willingly went back to said madman and is having his child, yet raises the boy as his own. After following his wife and son to America a week after they departed, he watches her die in his arms literally the day after they’re reunited. And yet Raoul is the one who gets punished for trying to save someone from being robbed and murdered? I mean, I know Raoul isn’t the sexy bad boy that the Phantom is, so I can’t expect him to be the object of all that “Christine/Phantom” fanfiction. But does that mean the man has to be an involuntary eunuch? It seems unnecessarily cruel to me.

And finally, let’s address the 10-year-old elephant in the room. Christine’s and Erik’s love-child Pierre isn’t much of a character in the book, which is understandable because this is a maudlin story between ex-lovers and he is 10 years old. We know from his limited scenes, however, that he is a very intelligent child who excels in music and in mechanics. (This is one aspect from the books that made it into the sequel; Leroux’s Phantom created mechanical wonders to trap Raoul during his rescue, and the Phantom makes similarly fantastic marvels for various Coney Island park owners.) He deciphers a clue left by Erik by taking apart a music box and reassembling it to play a hidden message for Christine. And he absolutely adores his mother with whom he is very close. By all accounts, he is a model son. But during the climactic scene of the book, as his mother lies dying in his adoptive father’s arms and he learns his true parentage, Pierre is given a choice. Raoul tells him he can return to Paris with him until he is of age, or he can stay with his true father, the Phantom. And incredibly Pierre chooses to stay with the Phantom, a man he has basically just met over his mother’s still-warm corpse, and grow up in America, a country he knows nothing about which speaks a language he struggles with.

I understand the symbolism of the situation: that Erik gets to keep a part of Christine that lives on in Pierre as well as gaining a son to whom he can pass on his fortune and his love. And now Pierre can be with a teacher who can bring out the best of his genius and talents. But Pierre must have inherited his mother’s brain disease when it comes to making inexplicably baffling decisions. I find it hard to believe that a young boy would willingly give up his home, title, and the only father he’s ever known so quickly.

Leaving the family drama, let’s talk for a moment about the conversations between characters and literal gods. Both Erik’s accomplice Darius and Pierre’s teacher Father Kilfoyle have conversations with Mammon, the god of gold and greed, and God, respectively. This might not be so strange in a story where the Phantom amasses his fortune by manipulating the stock market, except that these conversations reveal important details. Darius learns in his hookah-induced encounter that Erik is planning to pass his vast wealth to his son instead of Darius because Mammon tells him so; similarly, Father Kilfoyle learns both the Phantom’s real name and that Erik must be saved by love “beyond gold, self, and a woman he cannot have.” God is, of course, meaning Erik’s love for his son, but neglects to tell Father Kilfoyle that tiny detail. Both of these scenes are more for character development than furthering the plot, but it’s nice to know the truth about the existence of gods in the Phantom Extended Universe.

And because we’re talking to god and discussing higher themes of love, good and evil, and sacrifice, Father Kilfoyle can’t help but ask God why He allows evil in the world. In response, God basically tells the priest that, even though God has the power to make everyone good and loving to each other, he doesn’t because that would make life a boring paradise, and then there would be no difference between life on Earth and Heaven (which is somehow a bad thing). As far as establishing a canonical theodicy, God’s explanation is at least consistent with the original’s theme (the Phantom had to choose to show mercy and selflessness). But the fact that God could change the world for the better and apparently chooses not to is a weird element to include in The Phantom of Manhattan.

To me, however, one of the most baffling inclusions deals with how this book ties itself to both Gaston Leroux’s original 1910 novel and Webber’s musical adaptation. As I was nearing the end of the book and the penultimate chapter set up the final confrontation between its characters, I was a little surprised that the book’s final chapter began with a 40-year time jump and a long and boring lecture about the importance of integrity in journalism. The speech is given by Charlie Bloom, a reporter character who has up until this point been one of the narrators of the book’s events, albeit several decades older, so I knew this was not a chapter inserted from another book. But the shift was so abrupt and strange in what is a pretty straightforward book (and I’ve read some pretty strange books). When he finally picked up the story’s conclusion, I was satisfied (that there was an ending, not with the ending itself) but still a little confused. It wasn’t until I went back and read the preface written by Forsyth that I understood where the hell this came from. So I guess that one’s on me.

In the introduction to his book, author Frederick Forsyth spends twenty-six pages revisiting the original story (as if anyone who wasn’t already intimately familiar with the original would have even picked up this sequel). However, he primarily does this not to merely remind readers of “the story so far,” but to deride the inferior way in which Leroux chose to tell the story of Christine, Raoul, and the Phantom. He especially feigns astonishment at Leroux’s decision to begin his book by stating that the following events are true and were gathered by the author through his investigative work. Obviously this is a literary device by Leroux to add to the mystery of his ghost story, yet Forsyth approaches it as if Leroux had literally believed he was unearthing a real story. I suppose we could assume Forsyth is similarly using a literary device of his own to increase the legitimacy of his story, but this accusatory inception seems unlikely given the rest of the book. But then Forsyth goes a step further by literally stating that not only was Leroux telling this story poorly, but that Andrew Lloyd Webber was the one who told it the right way:

“So Andrew Lloyd Webber went back to the original story, pared away the unnecessary illogicalities and cruelties featured by Leroux and extracted the true essence of the tragedy… Looking at his original text today, frankly one is in a quandary. The basic idea is there and it is brilliant, but the way poor Gaston tells it is a mess.”

So taken alongside the lecture from the final chapter and its assertions that good journalists “should always try not simply to see, to witness and report, but to understand…the events you are seeing” and that “your masters must be Truth and the reader, no one else,” the demeaning of Leroux and the exultation of Webber becomes clearer. Even in the universe of the story, Forsyth wants everyone to know how great his boss is. Forsyth concludes his preface by announcing “This is the story of the Lloyd Webber musical and it is the only one that makes sense.” I suspect this introduction along with the final chapter has less to do with creative storytelling and more that Forsyth may have reeeeally wanted his story turned into the next blockbuster musical.

In the end, Phantom of Manhattan is irrefutably a sequel to Webber’s show and not Leroux’s original book, no matter how much Forsyth attempts to insert his sequel into the Phantom’s Extended Universe. If for no other reason, Phantom of Manhattan cannot be a sequel to Leroux’s work because (spoiler alert) the Phantom dies at the end. Leroux, acting as in-universe investigator of the mysterious events surrounding the Opera, learns the circumstances of the Phantom’s end. Similar to the Webber show, Erik kidnaps Christine to force her marry him, but lets her go after she shows him the first genuine kindness he’s ever known. In the book, however, Erik is so overcome with love that he rapidly and melodramatically begins to die. As his last act, he leaves explicit instructions to both Christine and another character, the Persian, concerning what to do with his body after he dies shortly after the events of the story. Leroux tells us that recently, 30 or so years after the event while he’s compiling his work, city officials discovered an old skeleton by the shore of the lake under the Opera’s cellars. Leroux indisputably identifies the remains as those of Erik, both by its proximity to Erik’s home and by a gold ring on its finger that features in Erik’s final instructions to Christine.

So with the Phantom dead (from…too much love?), there is no room for a sequel with him in it. And the book’s ending is not ambiguous, as Webber’s musical is. The Phantom does not disappear into the night; he is literally a pile of bones. Forsyth tries to retcon this in his introduction by asserting that Leroux assumed the skeleton must belong to Erik, and that he’s a bad storyteller because of it. Not like super sleuth Andy Webber, anyway. But the fact remains that, as much as Forsyth might protest otherwise, Phantom of Manhattan is only a sequel to Webber’s version of the story, because in the book the Phantom is dead, even if for a stupid reason.

Aside from this large issue, there are smaller aspects of the story that were just as baffling but not as egregious to enjoying the narrative. The idea that the great musical genius of the Paris opera house would be working on Coney Island, walking around in clown makeup and big floppy shoes instead of his trademark mask and cape is almost too funny to believe. The cameos of famous historical figures awkwardly inserted into scenes feels more like MadLibs than a serious novel (“We had a party, and Teddy Roosevelt was there!”) The fact that the Phantom writes an opera about the Civil War is something I’m torn on. On the one hand, the novel takes place in 1906, and the idea that the Civil War would be good material for an epic opera doesn’t seem that far-fetched. Both Birth of a Nation and Gone With the Wind prove (in different ways) that the mythical nature of that conflict long outlived the people who took part in it. Still, it’s just weird to me to imagine an opera so good that it makes the entire audience weep about such a terrible event in the relatively short history of the US. It just seems like, at the turn of the century, such a story would feature a little too much of the “Lost Cause” myth for my taste.

And finally, despite Forsyth’s best efforts, Manhattan is not as Gothically scary as 1880s Paris. I literally cannot find the idea of a caped Erik creeping around the waterfront warehouses or brooding in the penthouse of the city’s tallest skyscraper creepy enough to justify it as the setting of the Phantom’s second act. Unless he’s swinging on rooftops like Batman, Erik is walking the unforgiving streets of New York, and no amount of genius is saving him from getting mugged on the subway.

Finally, I want you all to share my frustration at the very last mystery of the book. In a short epilogue, we learn that during the First World War Erik and Pierre changed their name from Mulheim “to another, still widely known and respected in America to this day.” We are never told what this name is, but are given clues that they used their tremendous wealth to create a giagantic corporation which “became famous for its philanthropy across a wide range of social issues” and that Pierre married once and “died of old age in the year the first American landed on the moon” and “his 4 children live on.” Despite the (probably correct) suggestion by Julia that this was most likely just meant to be a general “happily ever after” and not some revisionist history of a famous American family, I cannot tell you how much time I spent online trying to find out what year the Rockefellers became rich or how many descendants Andrew Carnegie had. My search has so far been fruitless. In this way, it’s the perfect end to this book.

Other Sequels

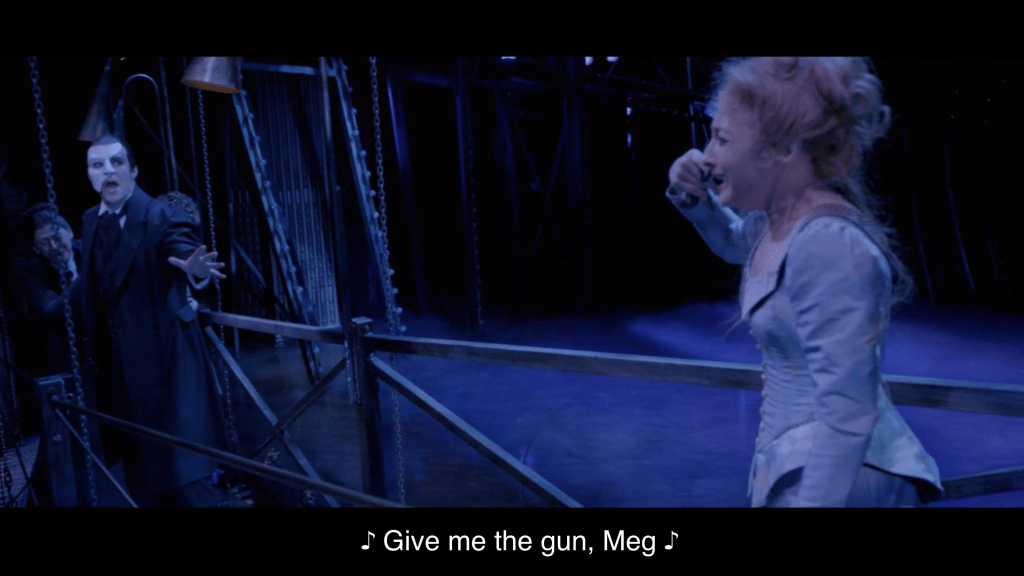

We can’t talk about a sequel to Phantom of the Opera without talking about the sequel that was actually made, 2010’s Love Never Dies. As stated above, The Phantom of Manhattan was commissioned specifically as an outline for a potential musical sequel to Phantom, and though many elements were eventually changed for Love Never Dies, some of the main plot points are the same. Christine and Erik still have a secret child (now called Gustave, as if Pierre wasn’t French enough), Erik is still living in Manhattan and tricks Christine into returning to him, and Christine still dies in the end after which Gustave decides to live with his biological father.

But there are some major differences as well. The Phantom spends the entire musical on Coney Island writing music and building wondrous machines instead of simply using it as a stepping stone to fame. Raoul is a main character in this version, although he is a total ass. He encourages Christine to go ahead and sing even after it’s revealed Erik is behind the entire thing, because he’s blown all of their money on drinking and gambling and is in deep debt. If any Raoul deserved to be shot in the groin, it’s this one. Meg Giry is also more prominent in this version, taking the role of Darius from the book as the jealous protegee who feels she deserves the Phantom’s riches and recognition. Meg goes a step further, however, attempting to kill both Gustave and herself in a murder-suicide and then accidently killing Christine anyway.

On a thematic note, the book makes it clear that Erik cannot have Christine and she does not want to be with him instead of Raoul. In the musical, on the other hand, Christine is given a choice between Erik and Raoul and ends up choosing Erik. You can draw your own conclusions about what this says about Christine, but she ends up dying soon afterward, so it doesn’t really affect the plot.

This musical does have one of the best opening numbers I’ve ever seen in a musical, and despite the fact that the show inadvertently saves the best for first, I can’t help but listen to “Til I Hear You Sing” on repeat.

In the end, Love Never Dies was not well received by fans and critics, even with a large overhaul after its first London run. Nevertheless, Andrew Lloyd Webber presumably made a ton of money. So I guess the whole endeavor (Manhattan included) could be considered a success. If you want a more thorough look at the musical, I’d recommend Lindsay Ellis’ excellent video on the subject.

It’s also worth mentioning that author Christine Pope published a sequel, Ghost Dance, back in 2020. I haven’t read it yet, but after spending time rereading both the original Leroux novel and Forsyth’s sequel, I’m interested in seeing how another author not beholden to Andrew Lloyd Webber envisions the story’s continuation. If nothing else, I’m thinking Ghost Dance might be a better novel overall, if comparing their respective GoodReads reviews are anything to go by.

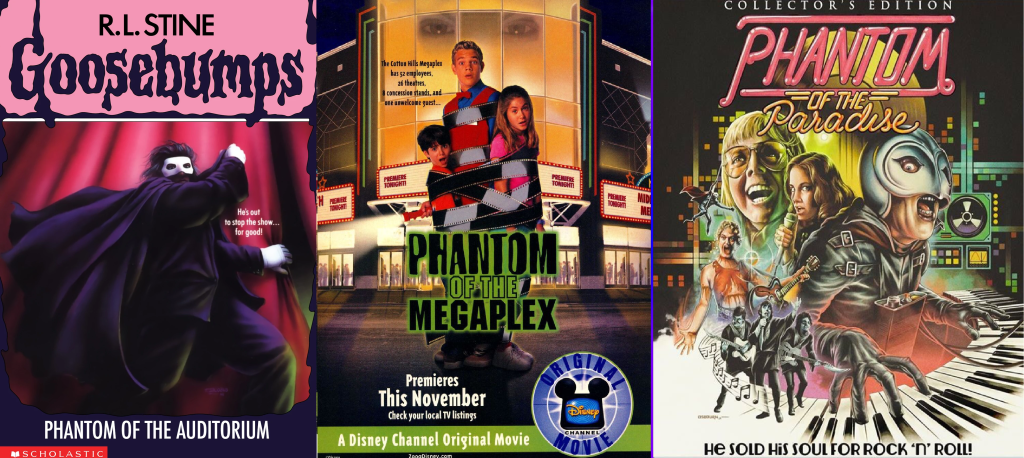

So read the original book. Read one of the sequels. See the shows (before they leave Broadway!). Find Phantom of the Megaplex on Disney+ or “The Phantom of the Auditorium” on Netflix. Watch Charlie from It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia not know who the Phantom is. However you do it, enjoy some sort of Phantom-related fun this Halloween.

And with that, we come to end of our Semi-Sequel Series. I had a lot of fun exploring the different ways franchises, their authors, and ideas for sequels can change direction, leaving unique stories behind in their wakes. Can you think of a semi-sequel that I might have missed? Leave a comment about what I should read next.

Happy Halloween and good reading!

Pingback: Semi-Sequel Series: “Jurassic Park” and “The Lost World” – Culturally Opinionated